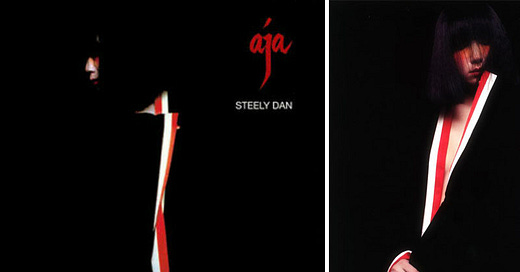

Album of the Year, 1977: Steely Dan, Aja

Sharing the things I know and love with those of any kind

Album of the Year is a planned recurring column that examines one album from each year of my lifetime and digs into what it means to me and others, whether it's a well-known popular favorite or a half-remembered niche obscurity. This installation concerns two caustic-yet-wistful control freaks and the album that helped me love them.

===

Steely Dan occupy this paradoxical space in pop music: a multi-platinum household-name band that has won all the awards and been firmly ensconced as music-biz favorites and is considered part of the mainstream rock canon, yet still feels kind of cultish. It is A Thing to be into Steely Dan -- not just A Thing, but A Thing On the Internet, the band becoming the beneficiaries of a lot of analysis and enthusiasm and jokes that might be kind of schticky and cloying if they didn't so often rise to meet the band's own air of sardonic, self-conscious tendencies. Maybe there's some irony-poisoned flailing at the margins of this enthusiasm, the same kind of efforts that built a cargo-cult pseudo-Dad culture around stuff like The Sopranos and Master and Commander that wind up too inflicted with teen-brained memery to fully pull it off. (Maybe because this perspective doesn't spend enough time considering the possibility, like the Dan did, that dudes rock is a counterfactual.) But I think people can appreciate that the Dan are funny on their own terms, and how Walter Becker and Donald Fagen were, especially in their initial '72-'80 run, absolutely peerless when it came to breaking the kayfabe of sophisticated cool. There is a lot to be gleaned from how they revealed all the sordid tendencies and desperate social signals thrown out by the people who think they're part of that world, or at least very well could be if they got their shit together just a bit more.

I think Aja is their best album. Or at least it's my favorite, which might be contentious enough a statement for Gaucho partisans that I kind of want to keep it low-key that my second-favorite is The Royal Scam. But I put that out there on the record anyways. Here's an excerpt of what I had to say about Aja when I ranked their discography for Stereogum in 2015:

This, of course, is The Big One -- they've got it in the Library of Congress's "culturally important stuff" record crates, it got a lot of people up at MCA walking into Maserati dealerships, and it probably made a lot of CBGB's-haunting New York critics really, really fed up. But it exists, it's ubiquitous, and it's goddamned beautiful, so what can you do. This is where Steely Dan fully redrew the parameters for sophistication in the midst of pop music's weirdest year to that point, and realized that their best eyes have always been aimed at reflections. [...] You can get this record pretty much anywhere and spend a lot of time trying to decrypt its odd little mysteries of mostly disappeared yet still familiar lifestyles. You might not get all the way down to the core, but there's plenty to help string you along if you think you've got a chance to. [...] There's nothing like an album that feels both omnipresent and still more or less just a series of startling out-of-nowhere ambushes.

That's just me, though -- there's plenty of other perspectives. A recent prominent one came via Alex Pappademas and Joan LeMay's book Quantum Criminals, which breaks down their discography in a pretty holistic and thorough kind of way. (As an aside, shouts out to Joan not just for her illustrations, but for actually going in on a really good cover of "Dirty Work.") And there's another Substack called Expanding Dan that is basically an incredibly in-depth fanzine with accompanying podcast; it's the kind of thing that makes me realize that I can be a huge enthusiast about something without ever feeling quite like an authority by comparison. So we have kind of a surplus of Steely Dan Analytics (Danalytics?), and it does drive home how engaging it can be to take something that seems pretty popular, find out all the curious bits of unease and conflict and surprise and revelation lurking beneath the surface, and go kind of overboard with it. But the question I'm interested in asking is: how'd I get here with the rest of them?

Now the funny thing about Aja for me, personally, is that it it dropped a couple days after I was born. This makes it literally the first really notable album released in my lifetime, or at least the first one I have a real strong emotional connection to. Maybe more a series of emotional connections, actually. Because release-date proximity notwithstanding, I don't think I was born destined to like these guys. It was a journey, one that parallels the way a lot of dedicated music fans evolve taste-wise not just for this band but for any band they take a while to realize actually speaks to them. I think I can break it down into four distinct stages for me.

STAGE 1: The Mysteries of Adulthood

I don't remember the first Steely Dan song I heard, and I am not entirely sure what the first Steely Dan song I liked actually was. My parents didn't own an actual copy since their record-buying budget was pretty limited when it came out, but my mom recalls someone giving her a tape with cuts from both Aja and Katy Lied that was later recorded over. My stepfather, a jazz head who introduced me to John Coltrane and Sun Ra, never had much to say about them; his idea of what was compelling circa 1977 was Wildflowers: the New York Loft Jazz Sessions so Walt and Don's pop sensibilities might've been understandably at odds, Wayne Shorter's spiritual-thunderbolt presence on Aja's title cut notwithstanding. So Steely Dan really beame a presence in my life the way they must have for a lot of other people my age: as a strange, intermittent, context-absent presence that occasionally manifested itself on the radio.

I spent a lot of my grade-school getting-into-music years -- the crucial "what else is out there besides my parents' collection" phase -- sort of split between contemporaneous MTV-driven Top 40 and the format that would eventually calcify AOR into the canon of "classic rock." That latter category fascinated me in that it clearly seemed to hew to an aesthetic ideal that was clearly out of date, but since I saw a past I hadn't experienced as more a curious place to escape to -- the world as it existed before me -- than a dying realm to run from and reject, it provided this distorted yet compelling look into what the adult world could actually be like. Since I was young and only haphazardly educated in recent history, what I remember internalizing at the most base level was that this was an idea of "adulthood" at its most intense, that the screaming guitar solos and alien analog synthesizers and enigmatically worded yet clearly emotionally unguarded lyrics represented some heightened level of sophisticated expression worth immersing myself inside. It wasn't until much later that I got the impression that I was making the kind of mistake that might've otherwise doomed me to committing some of those insufferable "I was born in the wrong generation" lamentations you see in YouTube comments of any song more than 20 years old. But in the end I only really had to fight to unlearn two ideas that I developed this way when I was young: one, that the Doors were geniuses (they were actually pretty dumb, which does still help me like them on a different level than I used to), and two, that Steely Dan were cornballs.

But I suspect that second lesson was one I didn't have to worry about at first, because when I think of my eight-year-old self taping my favorite jams off KQRS, I know for a fact that "Josie" was one of them. It was just so enigmatic: how it opened with this exotic, almost disorienting intro that sounded like it was going to lead me into this sinister realm of excess and disruption, how this alternately flat and wildly careening voice turned all these phrases that seemed like they should mean something but god knows exactly what ("break out the hats and hooters"; "shine up the battle apple"; "She prays like a Roman with her eyes on fire"), and how it made a big deal about the presence of a woman whose only described quality is that she's the catalyst for a kind of hedonism I wouldn't even begin to comprehend for several years. I liked something about the groove, though I couldn't quite put my finger on it yet; I had a vague knowledge of something called "disco" that people thought was stupid and another something called "blue-eyed soul" that seemed like it's supposed to be artificial, but I wasn't sure if this was either of those things and even less sure of what it would mean if it were either. I did get a kick out of Becker's guitar solo, though, and the way Fagen's voice seemed to punctuate the lyrics in ways that added some additional evocative bravado to the works, though it took a while for me to not be mildly irritated by the way he appended that additional sharp-squawked "no" to "she'll never say no."

By the time I was making home-listening mixtapes for myself in high school it was this song, even more than my other two formative Dan faves "Black Friday" and "Do It Again," that seemed to have the most appeal to me. And yet for the most part, the rest of their discography -- at least, the stuff big enough to make the playlist of a post-Lee Abrams classic rock juggernaut of the late '80s/early '90s -- left me cold, these weird oily intrusions into a space I found more compelling for its noisier and more acid-fried mutations of rock. Tuning in hoping to hear "Iron Man" or "Purple Haze" and getting "Rikki Don't Lose That Number" instead felt disappointing. And eventually I'd find out how many people were out there who agreed with me.

STAGE 2: Youthful Mistrust

There were a lot of complicated and irritating things about coming of age in the '90s, but the prominence of punk rock culture as central to being young and alienated ranks pretty high up there for me. My difficulty in trying to navigate all the contradictions of that world might actually be one of the bigger recurring themes of my music enthusiasm: how it felt simultaneously revolutionary and conservative, welcoming to misfits and quick to police them for digressing from the rules, the voice of disaffected youth that had already been the voice of disaffected youth not just ten but twenty years before I really started to contend with it. But I get it in that it just feels more appropriate to be into, say, the Ramones or the Replacements or Green Day than Steely Dan when you're a teenager because Steely Dan is not teenage music. It's not about all the feelings that come with early relationships, or the impatience over waiting to finally be granted some real autonomy, or the dawning realization with every passing news story that there is a more dangerous and shitty world out there than you might've initially assumed. And even if it was, I mean… listen to it. Imagine a seventeen-year-old putting on Countdown to Ecstasy and using the phrase "kicks ass" to describe it. I mean, it almost does, or at least "Bodhisattva" and the solo in "My Old School" do in a pretty liberal definition of the term, but you do not Get In The Pit to it. So you shrug it off.

And since teen brain can last well into your twenties, that skepticism lingers there. The spaces where you learn about pop culture and try to form your affinities? They back up those suspicions constantly for as long as the surliest Gen Xers hold the reins of discourse. Imagine contending with what Steely Dan meant in the 2000s: everyone your age thinks it was an absolute travesty that Two Against Nature beat Kid A and The Marshall Mathers LP at the Grammy Awards. Tom Scharpling makes his distaste for them a running gag on Best Show. When Mark Ames got mad enough at Chuck Klosterman to spur a 3000-word tirade about his writing for New York Press, one of his big gotcha examples of Chuck's "stupid lies" was when Chuck claimed Steely Dan were "more lyrically subversive than the Sex Pistols and the Clash combined." Dude-humor purveyors from comedy kingpin Judd Apatow to cult webcomic author Chris Onstad positioned The Dan like pretentious grotesqueries, even though the jokes seemed like the kind that required at least a little bit of carefully masked affection for their music behind some specifically character-based disdain. And at a moment when people were finally starting to internalize that maybe dudes aren't alone at the center of the music-fan universe, the conventional wisdom that women aren't into Steely Dan -- a statement that still somehow vaguely scans as legit even though a lot of us probably know at least a couple exceptions -- just added to their rep as solipsistic and inscrutable, snake oil peddled by our most irritating dickswinger audiophiles. Even when the jokes start to come from a place more fondly sympathetic than cynically resentful -- shouts out to Steve Huey and the Yacht Rock crew, who memorably portrayed them as the put-upon yet vengeful nerds bullied by the popular-jock Eagles -- the impression will linger that this music is deeply uncool. And then one day you wake up, you go about your day, and you hear a Steely Dan song you hadn't cared much for before and think wait, this is pretty good, and then the questions start.

STAGE 3: The Revisionist Moment

People tend to come around to Steely Dan in a few distinct ways. For our very online moment the most prominent one is rooted in irony, though it's also the perspective a lot of people around my age had to approach it with well before social media. In a Rolling Stone interview based around Quantum Criminals, Pappademas and Rob Sheffield claim that's the route they took, pairing the "ha ha, what if I got into Steely Dan" winking-eyeroll with the lingering embarrassment that comes with recognizing one is no longer Young and therefore might as well get with the program vis a vis Becoming Your Dad. It's only once they're in the thick of it that they realize, oh yeah, this is actually interesting stuff that speaks to them. (To paraphrase The Onion's best-ever joke about porn, Ironic Katy Lied Purchase Leads To Unironic Pathos.) That's the social-anxiety mode, where you question whether you should like something based on its rep and what your friends say and what the experts say and what pop culture says and all the other effluvia that floats around when people who aren't into them still feel perpetually compelled to have something to say about them.

But irony has a competing impulse that often goes unremarked upon in these kinds of questions of taste. It's not quite the opposite of irony -- it's not unvarnished, uncomplicated sincerity, at least initially -- but it does its best to bypass irony, or at least make a case for something without having to rely on it. Basically it's just the simple tendency to take something that seems uncool but contains at least a little indication of something you sincerely recognize as your version of cool, ask why do so many people believe this is uncool, and then try to reconcile those peoples' perspectives with the ones you try to form independent of them as you engage with the work on its own terms. And while I can't say for certain that there was no ironic intent in my getting into Steely Dan -- I do think there was at least some "liking things the snobbiest tastemakers hate can be fun" positive-contrarian impulse in there -- I find it hard to recall exactly how I felt about them before I got to the point I'm at now. For me they're a heavy-rotation favorite I think are clever and cryptically alluring beneath the sleaze and ennui, incredibly smooth but with a perfectionism that's less blandly clinical than it is compellingly neurotic, coming from a perspective that is humorous and cynical but too struck by the possibility of vulnerability to be a cheap easy joke. And I'm hard pressed to pinpoint what they represented to me before they finally became that in my mind.

I guess their rep for me in that interim between cornball and genius lied in the margins somewhere -- the sort of transitory space that tends to emerge when you start to filter your impression of the past through someone else's repurposing of it in the present. In my case, that meant samples -- and that's simple enough, maybe, the idea of ripping out all the context and baggage and background of a song to isolate one specific trait of it that really works, almost acting as a reset button to recalibrate your impression of the whole. It's probably possible to enjoy De La Soul's "Eye Know" or MF DOOM's "Gas Drawls" or Anthony "Shake" Shakir's "Arise" without ever really extending an appreciation of their production tricks to Steely Dan proper. (It is definitely possible to enjoy Lord Tariq & Peter Gunz's "Deja Vu (Uptown Baby)" and be actually mad at Steely Dan.) But if someone hears something in them worth revamping or repurposing or reinterpreting, it starts to really highlight what Steely Dan actually represent unto themselves in a musical landscape that seems pretty stark in its relative absence of other stuff that actually sounds like them.

One online acquaintance once expressed total bafflement at the idea that these guys really took hold of the millennial imagination when there was all sorts of more provocative and noisy music out there available to them. (This online acquaintance was not Steve Albini, but I think their tastes align pretty closely.) My rebuttal is that when Steely Dan were popular, there were a ton of bands that sounded like them but not as good, while there was only a handful of bands like the Ramones who dared to do what they did and excelled at it. Now that dynamic's been inverted to the point where being an adenoidal miscreant singing about being a bored teenager is exponentially more popular and familiar and even safe than whatever the hell it is that compels someone to write the kind of songs that show up on Aja. It's not like we're being inundated by eight-minute jazz-fusion epics about escaping to a pastiche-Orientalist Shangri-La lodged somewhere between underformed superficial caricature and quest for genuine enlightenment in the year 2024 (or 2014, or 2004). And then all that's left is to have a friend point out that the perfect segue for a 1974 playlist is to put "Any Major Dude Will Tell You" back-to-back with Joni Mitchell's "Help Me" and the pieces start falling into place. Do people appreciate Joni with that same level of semi-performative demi-ironic self-awareness that they do with Steely Dan? They don't need to, do they?

STAGE 4: Sobering Relatability

I know I haven't discussed the actual music of Aja much per se here, even though it's literally been running through my head throughout the writing of this essay. Maybe it's already embedded in my mind as a you-get-it-or-you-don't sort of thing because I've lived with it for so long, even though I know it took some work for me to go from the latter state to the former. And it's a pretty well-traveled subject since they're considered something of a muso band, simultaneously engaging with chops-focused shop talk and a demi-poptimist affection for the session players who trad-rock types traditionally used to overlook. I've got my favorite little flourishes on most of the songs, some of which are gimmes (Shorter's solo and Steve Gadd's berserker drumming on "Aja"; the Jay Graydon guitar solo that Walt and Don labored over before finally picking for "Peg"; Michael McDonald's harmonies on same) and some of which are ones I don't see brought up as often (that Eno synth that buoys the outro to "Aja"; the Blackberries/Rebecca Louis backup harmonies on "Black Cow" and "Deacon Blues" that highlight how amazing women can sound harmonizing over this kind of stuff). There are a couple tracks, "Home at Last" and "I Got the News," that took longer to grab me as much since they weren't as ostentatiously showy, but they still click in subtler ways if I go for a front-to-back listen and it's fun to find more in these deep cuts when I weigh them against the rest of their discography. "I Got the News" is fun enough as the more fidgety and anxious cocktail-disco counterpart to "Peg" but "Home at Last" is the real hidden gem; a year after "Haitian Divorce" this is them playing cod-reggae to far classier effect.

But at the risk of being one of those critics who fixates on the lyrics at the expense of everything else, it really is what they say that makes the how-they-say-it so moving. Not to try and gatekeep, but I think there's one crucial thing about Steely Dan that bypasses the online-ironic vibe to denote a true connection to the music, and it's the realization that a lot of their songs aren't just about rougeish weirdos doing crimes -- they're deeply melancholy reckonings with the idea that bohemianism is the last refuge of the outsider and the burnout and the loser. It's an idea and a feeling as integral to their music as it is to The Smiths or My Chemical Romance, it's just for adult angst instead of its more widely mythologized teen version. It really hits if you are an adult, especially a middle-aged adult, and you still get stuck in that rut of feeling out of step with the rest of the world even though you're part of almost every demographic that American culture was built to flatter nonstop. Speaking as a convert to Judaism who sees my upbringing as a sort of secular education in a philosophical relationship to provisional privilege in America -- with Becker and Fagen joining the Coens, Albert Brooks, and Mad Magazine in that pantheon for me -- there's a lot in that almost.

Steely Dan have at least one truly stunning expression of this outsider ennui on all their albums running up to this: the late-to-the-party early mission statement of "Midnite Cruiser," the post-apocalyptic isolation in "King of the World," the defiant, bitter pushback against feeling cheap and disposable in "Night by Night," the reflectively tragic escapism of "Any World (That I'm Welcome To)," and a personal favorite, "The Caves of Altamira" -- that one's about a kid who finds awe in the ancient art he discovers while hiding from the outside world, only to realize once he's grown that he can't get that same fascination from it anymore. (So basically an inverse of my experience with this band's music.) But "Deacon Blues" outdoes all of them, and I get the feeling that it's become one of the ur-texts of this band -- maybe even the definitive one. It's about someone who wants so desperately to be cool, even though his notion of cool seems to be fading as the hip midcentury modern jet-age bachelor-chic world is vanishing into the rearview. And this desperation is so acute that he winds up writing what reads like an aspirational suicide note -- one that assumes dreams can be bought off the shelf, that you can find "the essence of true romance" in being up against it, that being a whiskey-soaked DUI fatality is the best way to go out, that even his self-penned demi-hip nickname is in itself a label for a loser. I've never felt quite that level of ideation or doomed dead-end futility, though I did try to learn to "work" the saxophone when I was a kid. (It was tough, and I gave up; apologies to Pete Christlieb.) But I've definitely felt a certain way about trying to roll with all kinds of bad feelings and alienation, and constructing a slipshod suit of armor out of my aesthetic fascinations in some effort to offset it.

And now I'm out there with the other fans, ironic and sincere, old heads who copped the original LP for its buck-cheaper-than-usual $6.98 list price and zoomers discovering them through streaming, and we're all sharing this enthusiasm with the sense that we are now in this meta-space where "Deacon Blues" sounds like the inner monologue of a person who retreats to "Deacon Blues" itself for solace. Maybe it feels weird knowing that this band once felt enigmatic and odd, and now they're one of the most enthusiastically and sardonically scrutinized groups of their whole time and place. But that makes sense -- Steely Dan's supposed to make you feel weird anyways, and at best, at least a little comfortable in your weirdness.