Album of the Year, 1980: Blondie, Super Groups In Concert Presents Blondie (Recorded Live In London)

Deteriorate in your own time

Album of the Year is a recurring column that examines one album from each year of my lifetime and digs into what it means to me and others, whether it's a well-known popular favorite or a half-remembered niche obscurity. This installation concerns how a band at the peak of their imperial phase can feel like a phantom decades later.

===

"Blondie will sell lotsa records. Blondie will be very rich. I am jealous. You are jealous. You don’t care. We are not happy. Nobody is happy. You will run out and buy this record. You will rewrite the lyrics of these songs in bathrooms and on graffiti-streaked walls. My mother would not understand this record. I don’t know what I’m talking about. Alan Freed died for rock and roll. Most of this is true, but some of it is very untrue. Sometimes it’s hard to tell which is which. Won’t you please help me?"

That's how New York Rocker's Alan Betrock concluded his review of Parallel Lines, the 1978 LP that sent Blondie on a startling trajectory from CBGB cult attraction to Actual Big Deal Hitmaker Sensation. Throughout the review, he makes a number of declarations (keyboardist Jimmy Destri's come into his own as a songwriter) and predictions ("Heart of Glass" will not be a disco hit) that he constantly interrupts with odd little interrogative self-retorts: True or False? Fact or Fiction? It reads like there is a lot of unease and defensiveness and bet-hedging at work here, the kind of confused/confusing mixture of hyperbole and ambivalence that reads now like the perspective of someone who has no idea what side of history they might land on and isn't sure whether to risk finding himself on the wrong side of it.

A little less than three years later, at the peak of their superstardom and a few months after their '80 album Autoamerican had started to sink in, the same magazine interviewed guitarist and co-songwriter Chris Stein, and its author Andy Schwartz seemed to figure out how history was playing out at the time. "The interview was in part prompted by Stein’s resentment at those of you who responded to the Readers Poll essay question with disparaging remarks about his group, i.e., as “Band Most Likely To Make You Heave,” or by lumping Blondie in with such tarpit behemoths as Rod Stewart, Pink Floyd, et al." As a music fan who, being born in 1977, has never known a world without heated conversations about bands "selling out" their place in a subcultural movement -- or at least never known a world without it until fairly recently -- I thought it was pretty remarkable how Stein navigated that nascent conversation, one that had become an overheated matter of life and death by the time I was in high school. This passage had him riffing off his experience appearing on Rodney Bingenheimer's show in Los Angeles and being subjected to the resentments of Cali punkers.

"Well, we started out playing a few records, and we took a couple of phone calls that were, like, 'you fuckin’ bastards, using your jeans money for heroin, you assholes' – so then we couldn’t take any more phone calls on the air. But a couple of people called and said, 'Well, a lot of kids out here feel like you let them down, that you were their own personal band, and you don’t do any surf music anymore' – I think it was basically down to not doing any surf music, no rave-up guitar solos. So we tried to address ourselves to that on the air, that we like to break things up, that this album was an experimental album made in a spirit of open-mindedness, that we could have made an experimental album like the Clash’s experimental album [Sandinista!], but that for us, doing like MOR stuff was the same sort of approach. I see a lot of punk and new wave people getting as stuffy as opera fans about what they will and will not listen to. I mean, what’s the difference if you’ve got some guy who’ll only listen to something that sounds like the Ramones and totally writes off everything else?"

So they set about being a different kind of subcultural entity -- one that refused to stay in one subcultural niche at all. By the end of 1980 Blondie had notched some big trans-Atlantic hits by trying their hand at early rap ("Rapture," equal parts cheesy and cool) and old-school rocksteady revival (their '67 Paragons cover "The Tide Is High"). This followed their breakthrough success with disco crossover, "Heart of Glass," that they subsequently re-instilled with the sense of pop-art weirdness that brought them to the table in the first place via the spaghetti western-goes-proto-HiNRG "Atomic." "The Tide Is High" wasn't even their first shot at reggae; 1979's Eat to the Beat featured a pretty solid stab at it, "Die Young Stay Pretty," which sounded a little stiff in the rhythmic sense but also in the capital-S sense so it more or less worked out in the end anyways. That same LP had a pretty solid stab at art-funk, too -- "The Hardest Part," which sounded like they were splitting the difference between Fire Ohio Players and Station to Station Bowie. They were neck-deep in a rapidly evolving Downtown NYC scene that was not just transitioning from mid '70s punk, but charting a path that pointed in countless possible directions out of decade-cusp new wave, too -- into hip-hop and avant-jazz and post-disco and whatever seemed like the wide-open future the '80s seemed to promise. It's like Blondie had internalized the atmosphere of chaos and identity-searching scenester/fashion mania embodied in the New York Dolls' "Personality Crisis" and went yeah, but we could probably pull this off without the whole "frustration and heartache" bit.

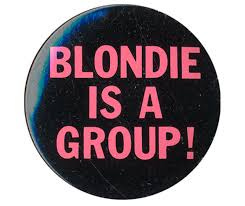

And they broke a lot of narratives in the process, thanks in part to just how singular their singer's role appeared to be. Debbie Harry had become a new wave pinup icon lodged somewhere between punk feminism and the male gaze; there she is on the cover of the February issue of Penthouse alongside such oh no headlines as "Women's Lib: The Male Strikes Back" and "Sex Change: If You Can't Beat 'Em…" Debra Rae Cohen's profile cracked that "Debbie is the first real female sex-object star that rock’n’roll has produced, making Janis Joplin, Bonnie Bramlett, and all previous contenders look about as hot as Rosalynn Carter." (Sheesh.) Well: that needless competitive comparison aside, Harry is gorgeous, the kind of gorgeous that typically comes after a lot of hard work and self-consciousness and experimentation and reinvention and collaboration and, finally, confidence. And as a complicated but probably understandable consequence she dominated the band's public image because of it, to the point where their manager Peter Leeds suggested a campaign emphasizing "Blondie Is A Group" just to remind everyone that there were, like, some dudes in the band who collaborated with her too. (The band thought it was an irritating idea, though probably in part because Leeds turned out to have a tendency to get on their bad side a lot.)

But speaking as someone who is also fascinated by pop-star swagger, it is not just that her beauty is attractive, it's also (and moreso) her cool -- her ability to branch out and occupy all sorts of unpredictable roles and mutations of the rock'n'roll sex symbol rep, where part of what makes her desirable is not merely glamorous but aspirational. Her artistic risk-taking wound up making her more enviable and inspirational than a lot of her male peers, even if she wound up having to carry herself a lot more carefully the hotter the spotlight seared her. The fact that her legacy has intermittently echoed through successors ranging from Madonna to Karen O -- or from Simon Le Bon to Julian Casablancas -- bears out some sense that her role in fronting one of the first great pop-punk bands was the culmination of some often-lost ideal, that being a pop star meant you could be Ronnie Spector and Mick Jagger at the same time. Harry didn't invent that, but she was one of the first to perfect it, and she made a point of complicating her own image and misdirecting people away from their assumptions. She wasn't a pure auteur like most venerated singer-songwriters have historically been, but she had enough autonomy to make it all feel like success was more or less on her terms. I still think it's a weird miracle that being one of the biggest stars of her time allowed her to work with David Cronenberg, John Waters, and Jim Henson -- and seem at home in all of their worlds.

The Pet Shop Boys' Neil Tennant coined the term "imperial phase" to describe a pop act at the absolute height of their powers, one that Tom Ewing appended to account for its fleeting nature ("a mix of world-conquering swagger and inevitable obsolescence"). And Blondie circa 1980 more than qualifies. They had the kind of presence that seems so indelible now that I feel like I must have been in thrall to it somehow, even though I'm sure it's retroactive because my awareness of pop music back then was maybe at most half a degree more sophisticated than that of your typical three-year-old. Still, one question lingers in the back of my mind, the question that leads me to write about them here in the first place: how big of a deal are Blondie now, really?

Yeah, they're famous enough and with a significant enough level fandom that I have been able to take advantage of a dedicated website which serves as a sort of press archive that rivals Rock's Backpages, which made this piece a hell of a lot easier to write. And they're having a bit of a moment again now that Chris Stein has an autobio out this month, which I've skimmed a galley of and found something wildly hilarious and/or weird and/or frightening on nearly every page. (Here's a fun little bit: "In New York we began recording our second record with Mike [Chapman], Eat to the Beat, at the Power Station and Electric Lady Studios on Eighth Street. It was then I discovered that there is an ancient stream running below Eighth Street that’s called the Devil’s Water. In the rearmost lowest room of Electric Lady is a little metal trapdoor that opens onto the stream. Jimmy and me tied a string to a plastic cup and pulled up some of the water that was horribly gross and had what looked like human hair floating in it.") Go back a couple years and there's that massive box set of their prime-era recordings that Numero Group put out -- which, considering that Blondie were candidates for being the Biggest Band in the World during the Jimmy Carter years, makes for odd bedfellows with Savage Young Dü and like five dozen comps of one-and-done 45s from short-lived regional funk bands. I like Caryn Rose's insightful assessment of the set (and the band) for Pitchfork, though it does read a bit like a (re)-introduction of the band to a potential readership that might not have actually known how much of an impact they actually had.

Me, I wrote about their (now-incomplete) discography for Stereogum in 2015 and came away from it thinking they were both better than they were often given credit for while also occupants of a surprisingly brief window of heightened success. (Their post-'82-breakup reunion albums they intermittently started putting out starting in the '90s aren't terrible, and they have some highlights, but they are very much Legacy Act kinds of records.) And that led me to the kind of questions I start conjuring up whenever I start thinking about how each generation's preferred nostalgia touchpoints begin to recede with each successive one's revisions. It's no secret that millennials have been going through an extended Fleetwood Mac/Steely Dan/Joni Mitchell phase, for instance, but do they give much of a damn about one of the greatest new wave bands to ever exist, or do they just consider Blondie their parents' version of the Meet Me in the Bathroom scenester bands they'd prefer to connect with as their own formative-years equivalent? And was the real Curse of Blondie the fact that they burned themselves out right before they were able to claim their stake atop the new pop world that MTV was building, that they never had the chance to take their place alongside the world-conquering mid '80s superstars who rescued the industry from its post-disco crash? That's the lens I want to examine Blondie through -- and my example comes not from one of their studio albums, but from a live concert that seems like it should be more epochal than its reputation.

This release of their show at London's Hammersmith Odeon on January 12, 1980 was originally part of the Super Groups in Concert series, a collection of live shows syndicated by ABC Radio Networks, recorded and aired as exclusive-for-radio programming in the late '70s and early '80s. It was subsequently bootlegged under a succession of provocative titles (Wet Lips & Shapely Hips in 1980; A Sexual Response in 1992) but never made its way into deep band lore the same way, say, the '78 show Television released as The Blow-Up or the Clash's extended stay at Bond's in '81 were. There's some intriguing background details: the TV show 20/20 was there shooting footage for a profile; Stein states in his autobio that there's more than 20 hours' worth that a filmmaker he knows is still trying desperately to track down. And for the next and final show during this three-night stand, Iggy Pop had been convinced by the band to show up and join in on a set-closing rendition of "Funtime" -- a song they'd already had some experience making their own, though I can't find the actual Hammersmith recording just yet. But it's hard to find retrospectives of this show that seem to give it any weight or substance, at least beyond an unenthusiastic missive from RateYourMusic by someone who thinks Eat to the Beat is "mind-numbing" and a similarly lukewarm AllMusic review that only makes matters more bewildering by getting the recording date wrong and referring to "Atomic" as "interesting, but not classic." It probably doesn't help that this set was eventually overshadowed by the BBC set they'd recorded just the previous month in Glasgow, rereleased in 2010 as an official document of the moment that supplanted the more ephemeral Super Groups broadcast and the boots that followed.

And if you let this set play out for a while, it doesn't seem especially exceptional at first. It does kick off in the best way possible, at least: touring behind Eat to the Beat means it only makes sense to open with the same song that kicked off the album, and "Dreaming" is a thing of wonder. A #2 UK hit that stalled out in the low 20s in the States, it's either a time-tested classic or an underrated deep cut depending on which side of the Atlantic you're on, and Stein/Harry put together something that rivaled Bacharach/David and Goffin/King when it came to sly popcraft. It gets you right away with a legit clever and hilarious opening couplet ("When I met you in the restaurant / You could tell I was no debutante"), then unfurls into this pop-poetic examination of how unreal love and creative ambition can feel, even when the person responsible for it is right there beside you. It's also one of the best "new wavers pick up what ABBA's laying down" cuts of '79 next to Elvis Costello's "Oliver's Army," one of those rays of proto-poptimist cross-pollination that tends to get deemphasized when people talk about what made the transition from punk to new wave so potent.

But as the set goes on, it's clear that this is Blondie in a very specific mode of superstardom, one where their first two albums are entirely absent from the setlist and the sharper, grimier edge of their origins is already starting to recede. "X Offender" and "Rip Her to Shreds" and "(I’m Always Touched) By Your Presence, Dear" probably still would've fit the mood -- "Denis" makes it from Plastic Letters as the sole pre-Parallel Lines hit -- but something about the moment called for a certain focus on the album that made them huge and the follow-up meant to maintain that momentum. If you're one of those sourpusses who thinks hooking up with Mike Chapman's Sweet-producing self was some kind of beginning-of-the-end moment, this is probably something of a drag. But if you ask me, there's something pretty impressive about putting out a two-hour-plus live set centered almost entirely around seventeen songs from Parallel Lines and Eat to the Beat and making it sound like the Greatest Hits itinerary of a band that took four or five years to come up with it all instead of one.

One catch is that this is not a redundant cursory runthrough of their latest and greatest. By emphasizing Parallel Lines and Eat to the Beat -- if not in full, then at least the majority of both albums -- it makes the deep cuts feel as important as the hits, and also lets them breathe a bit outside the confines of the studio. Not all of it is transcendent -- "Atomic" can never sound truly lifeless, but the version here feels like it's 90% of the onrush that the studio version is, at least until the guitars start getting a bit unruly during the breakdown and Harry starts putting a bit more oomph in the later choruses. But a lot of it spurs the classic record-geek this could've been a hit single too speculation, including the track "Atomic" does an abrupt transition into, "Living in the Real World," which brings some real oh so you Ramones fans think we've gone soft, huh energy with one of Harry's most self-aware and fierce performances. It's the kind of moment that can crystallize everything a band and the person who fronts it really represents: "Every day you've got to wake up/Disappear behind your makeup… I can do anything at all/I'm invisible and I'm twenty feet tall." It's a searing little exclamation point at the end of Eat to the Beat; here it's a lobbed bomb reminding these fans, many of whom may still be fairly new to the band, just who they're dealing with.

There are a lot of other moments like this, where the big numbers like "Heart of Glass" (which boasts a new Moroder-oid extended synth-arpeggio intro that Destri milks for a good minute or so to fantastic, crowd-roiling effect) and "Hanging on the Telephone" (always, always the reason power pop is worth believing in) and "Sunday Girl" (a surprisingly calm yet vibrant respite as the penultimate number) feel less like hits among filler and more like familiar landmarks in a sprawling metropolis. There's this fantastic early stretch where underrecognized album cuts "Slow Motion" (a jagged but propulsive new wave garage-Motown update) and "Shayla" (a wistful synth-soul ballad that sounds like their sci-fi-tinged take on of one of Patti Smith's Blue Öyster Cult collabs) and undercharting singles "Union City Blue" and "The Hardest Part" are played in a succession that fully takes advantage of Harry's thematic range. In succession she is the cool detached observer, the tragic-romantic empath, the awe-struck/awe-striking conduit of excitement, and the all-guts tough with big-heist ambitions. And while we're at it, shouts out to "Die Young, Stay Pretty" -- which they perform here an hour or so away from the Coventry epicenter of the 2-Tone movement but feels at least a few miles closer than they did on the LP. (The venue's dub-by-circumstance reverb helps, though the Clem Burke/Nigel Harrison rhythm section makes sure there's some weight beneath the echo.)

But then something pretty startling happens. Blondie always threw all sorts of covers into their itinerary; I've got a '77 live boot where they do a kickass version of Yardbirds' "Heart Full of Soul" and the Runaways' "I Love Playin' With Fire" and close out with "Moonlight Drive" in yet another piece of evidence that a lot of bands rock critics think were better than the Doors thought the Doors weren't as crummy as the critics said. There's another one from the Palladium in NYC, 1978, that's a bit closer to the punk-influence canon, where they close out with a three-fer of Iggy's "Sister Midnight," David Bowie's "Heroes," and T. Rex's "Get It On (Bang a Gong)" that runs an accumulated 20-plus minutes. But the stretch in this '80 Hammersmith set is wild in a sense that it seems to pit them in a certain space in the pop-history conversation that could take them just about anywhere. "Hanging on the Telephone" -- a cover itself, of course, a Nerves obscurity introduced to the band by Gun Club's Jeffrey Lee Pierce -- segues into ur-garage joint-trasher "Louie Louie," a song that once threatened to curdle into cliche through sheer omnipresence but is rescued from Animal House oafishness by Harry's line-toeing between aloof deadpan and uninhibited giddiness.

And then, in a move that would provoke a sea of aggrieved phone calls to the radio station of any DJ with the chutzpah to try this with the original studio recordings, they go right into a song a lot of rockists would consider the spiritual and aesthetic polar opposite of "Louie Louie" -- Donna Summer's "I Feel Love," a song that as of 1980 was both a spectre of the dying disco movement and the progenitor of the sounds that would succeed it, with Blondie in the middle negotiating those two worlds and introducing their own flourishes. Is it blasphemy to add guitar to the first great all-synthesizer hit? Maybe, but the only thing more impressive than the fact that it works is the fact that Harry, who is (like everyone who is not Donna Summer) no Donna Summer, still uses that characteristic high, airy part of her vocal range to do justice to the necessarily ethereal euphoria of the original. This wasn't the first time they'd covered it, though: years before they collabed with Moroder on “Call Me” and a few months before that '78 NYC Palladium show, they'd attracted the attention of Robert Fripp, who would join them for a May '78 CBGB's benefit for the recently-stabbed Dead Boys member Johnny Blitz and accompanied them on an early version that this later '80 rendition took to full fruition. (I'm still uncertain as to whether Stein or Fripp handles the lion's share of guitar on this performance, though whoever it is, he's playing like he's taking an industrial lathe to a gold brick.) Of course they follow it up with "Heroes," and of course it fits them, not just because Fripp is actually sharing the stage with them and reprising the sound that made that song so eerily majestic but because of course Blondie are believers in the Bowie model of pop stardom, of change and adaptability and the idea of putting an unreal quasi-commercial facade on music that is nevertheless deeply personal and artful. Only when they traipse through a slightly-too-arch version of "I Got You (I Feel Good)" does the spell finally break, not because it's no good (it's fine) but because it doesn't sound quite as startling and chaotic as what their downtown peers were doing with James Brown rhythms back home (whether we're talking no-wavers or hip-hop DJs).

A couple numbers later -- "Sunday Girl" and a droning rave-up of "Pretty Baby" that lands musically somewhere between Elvis Costello and La Düsseldorf -- and they drop a berserker rampage "One Way or Another" as the closer, one where Harry taps into her most monomaniacal theatrical side and ad-libs her way through a recursive, rapidly escalating, buildup-and-breakdown-riddled deconstruction of one of their most notorious hits -- the question hey did you know this song is about dealing with a stalker answered with an enthusiastic no shit, but this time the stalker is me. And then she casually works her way through a concluding bit of banter: "Ah well… I guess that's about it. Happy New Year, one more time… see ya 'round." It was like they hadn't just made a case for themselves as the band that could finally finish that long-in-progress bridge commercial pop and the avant underbelly of rock, a creative force that seemed to write and record new standards practically at will, fronted by an icon that seemed destined to define the next decade. It was just a hell of a gig, a real good time, more to come TBD. There'll be a next step someday, but that can wait.

Ten months later Autoamerican saw them experimenting their way into vulnerability -- it produced some hits but also some bewildered reactions, Robert Christgau lamenting "They got what they wanted and now what?" and Rolling Stone's Tom Carson absolutely savaging it like it was Chris Stein's monster ("such an anthology of intellectual onanism that it’s almost the rock equivalent of a godawful Ken Russell movie"). And then in '82 The Hunter landed with a plop after they'd attempted to soldier through all kinds of health and drug and creative problems and just couldn't sustain their energy anymore. Between the release of those two albums they'd perform a reggae-fied version of Teddy Pendergrass's "Love TKO" when they played SNL in '81 -- the same episode they pulled their star card in convincing Lorne to give a showcase to The Funky 4 + 1, making them the first hip-hop act to appear live on national TV -- but maybe "Bad Luck" would've been more apropos.

Still, there's something to be said for a band that more or less died young and stayed pretty while actually still surviving. History vindicated them to the point where it's almost unremarkably normal how it all panned out: the eclecticism and the line-toeing between underground and mainstream cultures that bothered so many people turned out to not only be one of their defining features, but one of the most prescient breaks from the direction that mainstream pop was being siphoned through, a middle finger to the narrowcasting that had threatened to drain all the genre-hopping adventure out of music during the cultural Jimmy Carter Interzone between '70s classic rock and '80s MTV. And at the same time, if Blondie are no longer as Big a Deal as they used to be -- if they're more influential cornerstone than omnipresent hitmaking machine -- then that at least somewhat negates the whole "sellout" conundrum. Instead they feel like something better than that, an important part of a pop continuum bigger than themselves. Blondie is a group -- but they're one of many, and they'd probably be the first to remind you of that.

Fine work as usual - got the itch to start trawling for live Blondie bootlegs, which is always the mark of good music writing for me.

And hopefully that gives me leave to be insufferably pedantic, for the band that covered "Love TKO" on SNL in '81 was not, in fact, Blondie. I mean, it was Debbie and Chris, so they probably coulda gotten away with calling it "Blondie 2" or "Bottle Blondie" or "Gallagher II" if they chose to. But it was really Debbie solo (though with none of the personnel or the Chic'd up sonics she brought to her actual solo debut, KOOKOO, that summer).

Here's who played:

Chris Stein (guitar), Georg Wadenius (guitar), Lou Marini (sax), Leon Pendarvis (piano), Chris Palmaro (organ), Marcus Miller (bass), Buddy Williams (drums), Errol "Crusher' Bennett (percussion), Janice Pendarvis (backing vocals)

Granted, Clem Burke DID take the drum seat for their second performance that night, a cover of Devo's "Come Back Jonee," so...

As you may know, Debbie was also the host of that particular SNL, the antepenultimate episode of the notorious [but begging for re-evaluation] Jean Doumanian interregnum, which means, of course, you get to see her trying out her comedy chops a good seven years before John Waters gave her a chance to do so for real. She's no Gilda Radner, natch, but if you ever wanted to see her whipping up some giddy Jersey energy to portray the love interest of Joe Piscopo's most transcendently annoying recurring character, or see her in a 1984 parody trying to deal with Big Brother asking her on a date via telescreen, there's your opportunity.

(And if you weren't perversely intrigued enough by that, please note that in the latter sketch, Big Brother is portrayed by... Gilbert Gottfried. In his normal voice. And not even squinting.)

You got me spending twenty minutes reading about Blondie, something I hadn't expected I'd do. Thank you. I never knew 'Dreaming' wasn't a bigger hit in the US, I'd always considered it one of the more well known songs—and probably my favorite. I think I need a revisit for the deep cuts.