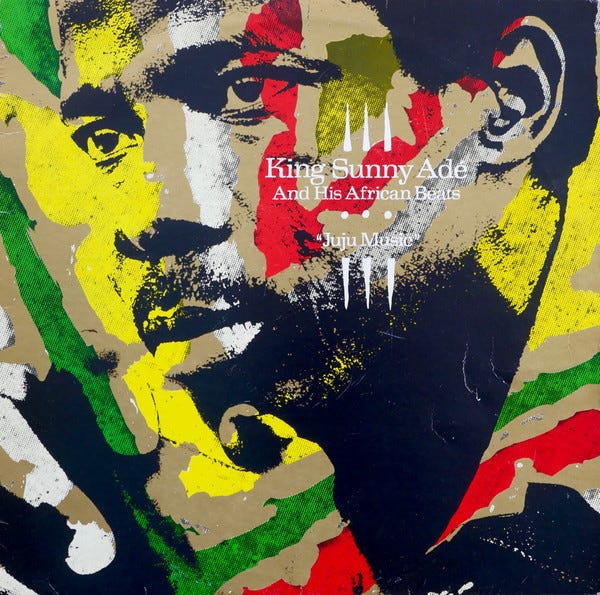

Album of the Year, 1982: King Sunny Adé and His African Beats, Juju Music

I understand it, fight for me

Album of the Year is a recurring column that examines one album from each year of my lifetime and digs into what it means to me and others, whether it's a well-known popular favorite or a half-remembered niche obscurity. This installment concerns the question of how to listen globally as a way to shake off provincialism.

===

"Why are you always playing this Italian music?"

This was the question I asked my mom one day back in the mid '80s when, for what must have been the umpteenth time, I'd heard Synchro System emanating from the little tape deck she kept in the kitchen. To be fair to myself I was maybe six or seven, and I wouldn't have the chance to play a Carmen Sandiego game for another few years, so my grasp of international cultural signifiers was still pretty shaky. Maybe I thought that coming up with the first foreign country I could think of to try and pinpoint this music -- music that sounded like nothing on pop radio, sung in a language I couldn't recognize let alone understand -- would make for a funny little way to needle my parents about their enthusiasm for it. The joke's on me, of course: not only would I learn that this artist and his band were Nigerian, I would develop my own interest in this music -- enough of an interest, at least, to find a lot of warmth and solace and vibrancy in it. Some of that might be familial connection, and some of it might be the necessary early steps towards a still-ongoing broader musical education, but it wasn't too hard for me to learn to love this music and meet it on its own terms by the time I'd picked up about three LPs' worth of it years later.

King Sunny Adé has more than three LPs -- far more. The ones that first stuck with me were the most immediately available ones, the trio that he released on Island Records imprint Mango: 1983's Synchro System, its 1984 follow-up Aura, and, most crucially, the 1982 breakthrough that stood at the forefront of Chris Blackwell's efforts to find the Bob Marley of African music. The Island founder had hopes to sign Fela -- who, even now, looms largest as the ambassador/figurehead/rebel with the most lingering international impact -- but after Arista's Clive Davis beat him to it, Fela's manager Martin Meissonnier suggested another artist he represented at the time. Per Robert Palmer in the October 10, 1982 New York Times:

Mr. Adé's new album, ''Juju Music,'' is being marketed worldwide by Island Records, the label that built the late Bob Marley into an international star and Jamaican reggae into one of the Third World's most profitable exports. ''There are around 1,700 modern bands in Nigeria, but Sunny Adé's seems to be the strongest,'' says Martin Meissonnier, who produced ''Juju Music.'' ''Island Records, and a lot of people in Nigeria and other parts of Africa, are hoping that Sunny will make an opening in the West for some of these other bands.''

The idea is not terribly farfetched. African influences have been more and more prominent in rock and jazz in recent years. African pop music and British bands heavily influenced by it are a full-blown pop fad in England just now. The time seems right for Sunny Adé. And once Mr. Adé gets a hearing, his lilting, lyrical, compulsively danceable fusion of traditional Yoruba drumming with a pop instrumentation that includes pedal steel guitar and synthesizer proves difficult to resist.

The article then goes on to give the reader a brief primer on Fela and what made his Afrobeat sounds so popular in the '70s before casting Adé's style of jùjú music as something of a shift in the zeitgeist. It's more a outwardly traditional form of Yorùbá music, less influenced by American funk and soul, yet still modernized and engaging with the present. And, at least according to the Times, it was becoming more popular among the emergent Nigerian youth culture of the '80s. Meanwhile Juju Music proved easy enough for American critics to both trace its lineage and find some unexpected resonances: dub reggae, salsa, even the twang of the Ventures. (My own nascent fumbling connect-the-dots attempt as a kid was the notion that the steel guitar on the album, played by Demola Adepoju, vaguely reminded me a bit of the one other familial album I knew with that prominent tonal presence: The Dark Side of the Moon.) This was the kind of context you could typically imagine being presented to underinformed yet curious American audiences: you know Talking Heads are into this stuff too, right?

If you missed that Times article, and just walked into a record store with no real notion of what this music was and walked out of said store with a copy of Juju Music in your possession because a clerk recommended it, the liner notes on the back cover would give you their own perspective. They played up the fact that Adé was a megastar in Nigeria, moving countless units and dominating the charts, and while his back catalogue was hard to find, it was vast enough ("the man has released some 40 albums during the past decade") to promise you that he was no fly-by-night flash in the pan. And if you wanted to know what the traditional core of this music was, the structures that made it what it was, this was also helpfully explained (albeit using a capitalization of the genre inconsistent with the actual album title):

JuJu Music is rooted in the complex call-and-response between the talking drums and the singers. Although the music has been around since the Twenties, contemporary JuJu Music really took shape with the introduction of Western instruments in the Fifties. Electric guitars, for instance, are now central. To Western ears the electric guitar is the dominant sound, its tunings and its harmonies lending a unique distinction. Other components include steel guitars and, more recently, synthesizers (which make an extraordinary blend with the traditional talking drums).

Sunny Adé, with his band, The African Beats, has pioneered many of the innovations in JuJu Music, constantly embarking on new ideas and using the full resources of the modern recording studio. The African Beats, for example, was the first band to use Hawaiian guitar, synthesiser and now, on this new album, even reggae-style Dub effects.

[...]"JuJu music is essentially party music… the fans out there want to dance and the rhythm is basically simple and, once you hook it up, it flows endlessly" says Sunny. "It really is a very rich music."

So that's some helpful context: why this artist is a big deal, how their music operates, its traditions, how it connects to other forms that might be more familiar to the listener, and a simple summary of the bandleader's own philosophy. That's just about all the information most listeners would really need, assuming they were already inclined to find themselves searching for something new outside the usual offerings of Western commercial pop music.

And yet one crucial thing was missing from all this coverage and promotion: a readily accessible translation of the lyrics.

Whenever I listen to a song in a language I don't understand, I'm always wondering what I'm missing without the capability to understand the words. I've invoked the "babies love to dance" argument before, and I still like the feeling that comes from being able to experience a different form of meaning through a singer's tone and timbre and performance that completely bypasses the presence (or burden) of the words' actual meaning. Still, hearing a singer's voice but lacking comprehension of the specificity of their message can still make listening to this music feel a bit detached, a degree or so removed from the immediacy that a complete comprehension can provide. And sometimes that gap can be pretty aggravating. Even now, when what's left of the usable internet can (theoretically) provide you with far more information to help you translate non-Anglophone works, I'm having difficulty sourcing English lyrics for Juju Music. This is pretty frustrating considering its place in the history and development and popularization of the whole concept of "world music" as a whole market segment of the record business. And I think the implications of this situation adds a conundrum to the whole phenomenon of world music that other forms of cross-cultural and international art aren't as susceptible to. Literature arrives to us translated, we expect films to be subtitled, but music is just there as it's recorded and performed -- and whether or not its lyrics are imparted to us in the language we understand is often treated as strictly optional.

Now it's a neat little thought exercise to try and pinpoint how long one can live with and enjoy an album without knowing the words. Pretty much every music enthusiast who crosses that certain threshold from casual listener to adventurous one winds up with at least a few albums like Juju Music in their collection, a record where this language barrier is more a mildly intrusive afterthought than a frustrating dealbreaker (see also Os Mutantes, Tatsuro Yamashita, or Cocteau Twins). One could make a case that Fela's music seems to hold more crossover appeal than Adé's these days in Anglophone regions because the former frequently sang in English and the latter in Yorùbá, but it's also not hard to get why Juju Music was considered a potential breakout record by the people at Island. It drew from and expanded on Adé's already-massive repertoire from the previous decade or so, distilling it all into the best possible highlight reel, and brought his music's most appealing aspects to the forefront. There's one English-language song on the album, a pairing of "365 is My Number" with the spacy instrumental dub-tinged vamp "The Message," and the simplicity of its love-song entreaties are familiar enough that the nuance is all in the harmonies Adé's voice leads anyways. The album follows a somewhat more West-compatible approach to his music, most notably differentiated from his earlier work by a focus on discrete individual songs rather than sidelong medleys and workouts. But its breaks with jùjú tradition aren't severe enough to sound like a Westernized compromise; it's a little more musically busy and hi-fi than his self-released '70s material but it pointed in a direction he actually wanted to go.

And it's gorgeous -- all riding off this fascinating balance of moods where the momentum is persistent, yet the atmosphere is calm and welcoming. That feeling was pointed out frequently in coverage of the time, how Adé and his band sustained this vibe that was equally attuned to bodies in motion and at rest, where it could provoke you to dance all night or invite you to lay back on a quiet afternoon. The billowy-yet-heavy timbre of the talking drums that round out the percussion makes for a solid backbeat that still carries a sinuous fluidity to it; often they sound as much bassline as beat. Adepoju's steel guitar is a major draw, a singular enough sound that he was able to showcase it on a headline-act LP that I absolutely need to track down and add to my regular rotation, and yet it's also Adé's own guitar that acts as its joined-at-the-hip counterpart: sharp and cutting in its emphasis, yet light-footed in the way it bounds across the polyrhythms and harmonizes with the steel to the point where their call-and-response feels inseparable. The synthesizers, meanwhile, are there not to be a crossover pop gimmick but an accent to the traditional musical ideas that predate it, just another way to bend tones and bust all the negative spaces between the beats wide open.

So yeah: the language barrier can be a little bothersome, but that in itself isn't necessarily the thing that made the push to popularize Adé's music such a gamble. It had precedent as an effort that built not just off Adé's history, but the gradual yet steady emergence of African roots in the pop music conversation. A generation before Adé, Nigerian percussionist Babatunde Olatunji released Drums of Passion on Columbia in 1960 and subsequently established the potential for African roots to become an important component of Western music. Throughout the decade, South African artists like Miriam Makeba, Hugh Masekela, and Letta Mbulu all served as ambassadors of a South African culture they were fighting to regain an autonomy for. And as Afrocentricity became a more visible part of diasporic Black culture in the West, that influence spread from its initial adoption into the jazz and folk worlds to inform the more commercial realm of R&B, to the point where it became impossible to imagine the sound of the '70s without it; go to a block party or a disco in NYC back then and if you didn't hear Manu Dibango's "Soul Makossa" at some point (or one of the myriad covers thereof) that meant you were dealing with a second-rate DJ. Marketing Adé as the next big thing made a lot of sense in that context, especially when it was emphasized just how many common roots Yorùbá music had with the stuff people heard every day on the radio -- not just R&B or dance music or reggae but rock and even country. It's incredibly versatile music with wide-appeal potential, not to mention a good way to engineer some unexpected but logical segues in mixtapes and playlists.

But the matter of breaking Adé turned out to be more complicated than just trying to find a common language or even a shared culture between an established artist and his prospective international audience. The big complications -- not all of them, but the most pertinent ones -- all came down to marketing. In the West, especially the United States, and especially especially in the relative provincialism of pre-internet culture, there's this tendency for the idea of "foreign" art to be pushed as something of an exotic novelty, and subsequently recieved with either touristy curiosity or wary skepticism. In this era, whether you were pop-friendly like Yellow Magic Orchestra or relatively countercultural like Gilberto Gil, there was an expectation that what they represented was distinctly bound by their national character in ways that might prove challenging to cloistered Americans. (A lot of U.S. critics were freaked out by how Scandinavian ABBA were, ferchrissakes.) That meant the coverage of these bands often had an air of diplomatic negotiation that could easily get somewhere between naively myopic and straight-up jingoistic from those less inclined to believe the hype. And some of the people who did buy into it ran the risk of blindly overstepping these cross-cultural lines en route to trying and sometimes failing to fully "get" a milieu they could only meet halfway.

Most people I know who are into multiple different styles of non-Western music -- my parents, my friends, various music-critic acquaintances -- tend to be a bit more discerning than the people who buy into the reductive version of this landscape. But the tourist listeners, the ones who seem to use this music's supposed "exoticism" as a means of distancing and othering, even as they demand "authenticity" at the same time? I still suspect they outnumber us. Christgau's reviews of Adé's Island albums play around with these perceptions, with his Juju Music blurb picturing a target audience of "amateur ethnologists, Byrne-Eno new-wavers, reggae fans, and hip dentists" -- the kinds of familiar yet trouble-signifying caricatures that might've had trust-deficit sufferers picturing the arrogant-bourgie subject of Jello Biafra's ire on the first verse of "Holiday in Cambodia." And I suppose it didn't help that one side effect of this push to make Adé the toast of the early '80s American college circuit eventually led to the fateful idea that his band would be a focal point of Robert Altman's dogshit-deluxe teen-party-bro farce O.C. & Stiggs, maybe the most baffling mismatch between a movie's tone and its choice of featured musicians until Digital Underground showed up in Nothing But Trouble.

This has been one of the more frustrating aspects of dealing with "world music." No less an advocate than David Byrne, who founded the Luaka Bop label specifically as a way to spread an enthusiasm for international sounds, wrote an article for the New York Times in 1999 lamenting that it was an impossibly restrictive category for an incredibly wide-spanning collection of styles:

What's in that bin ranges from the most blatantly commercial music produced by a country, like Hindi film music (the singer Asha Bhosle being the best well known example), to the ultra-sophisticated, super-cosmopolitan art-pop of Brazil (Caetano Veloso, Tom Ze, Carlinhos Brown); from the somewhat bizarre and surreal concept of a former Bulgarian state-run folkloric choir being arranged by classically trained, Soviet-era composers (Le Mystere des Voix Bulgares) to Norteno songs from Texas and northern Mexico glorifying the exploits of drug dealers (Los Tigres del Norte). Albums by Selena, Ricky Martin and Los Del Rio (the Macarena kings), artists who sell millions of records in the United States alone, are racked next to field recordings of Thai hill tribes. Equating apples and oranges indeed.

[...]

In my experience, the use of the term world music is a way of dismissing artists or their music as irrelevant to one's own life. It's a way of relegating this ''thing'' into the realm of something exotic and therefore cute, weird but safe, because exotica is beautiful but irrelevant; they are, by definition, not like us. Maybe that's why I hate the term. It groups everything and anything that isn't ''us'' into ''them.'' This grouping is a convenient way of not seeing a band or artist as a creative individual, albeit from a culture somewhat different from that seen on American television. It's a label for anything at all that is not sung in English or anything that doesn't fit into the Anglo-Western pop universe this year. (So Ricky Martin is allowed out of the world music ghetto -- for a while, anyway. Next year, who knows? If he makes a plena record, he might have to go back to the salsa bins and the Latin mom and pop record stores.) It's a none too subtle way of reasserting the hegemony of Western pop culture. It ghettoizes most of the world's music. A bold and audacious move, White Man!

With that in mind, watch this clip of Adé from UK TV's Channel 4 in 1984 and, when you're done, take a moment to ask yourself what the most fascinating thing is about it is.

Was it the gold Rolls-Royce -- the same kind of car Alice Cooper bragged about riding in all Yankee Doodle Dandy-style in "Elected"? Was it the fact that the interview he has in the back seat is about the logistics of getting enough money to make sure everybody in his band and crew is paid? Or was it the later demonstration and explanation of the talking drum -- which, in essence, is a literal example of music filling the role of language itself? Here Adé appears as both musician-as-businessman and musician-as-ambassador, and it feels like a knowing tweak of how "world music" stars are generally presented by the more cynical corners of media. He's not some mysterious rustic Third World Other, transmitting inexplicable sounds from foreign lands. He's a savvy and enduring pop music superstar -- nationally, then continentally, en route to globally -- whose concern over the potential to have anything lost in translation appears secondary to his confidence in being able to transcend it.

Even if Juju Music was a critical darling -- 4th in Pazz & Jop, outpacing the likes of Prince's 1999 and Marvin Gaye's Midnight Love -- jùjú itself didn't quite become the big thing that Island hoped it'd be. Adé earned little to no radio play in the States, and even the synthpop updates of Synchro System and the Stevie Wonder feature on Aura couldn't push his music past that crossover threshold -- at least, not to the same extent that, say, Hugh Masekela did with his '84 electro-funk dance chart hit "Don't Go Lose It Baby." In fact, that attempt to cross over might've posed additional problems. As Michaelangelo Matos's ‘84 pop landscape overview Can't Slow Down details, there was a sense that the Westernized touches Adé brought to Juju Music were starting to dilute what made him special when he ramped them up on his successive Mango albums. NYC-area show promoter Paul Trautman described it as "too staged -- they were trying to turn him into more of an American, British rock type. There was an unnatural quality to it. It's like they put cement shoes on him. There's a spiritual aspect in Yorùbá music and African music in general. You lose that. That's the quality that people are getting. They were no longer being transported." And it turns out that reggae was still the label's bigger meal ticket: it's worth noting that Aura, the final album Adé and his African Beats released under Island before getting dropped, came out the same year as the now-omnipresent Bob Marley best-of Legend. The college crowds Adé had found some success with would gravitate back to their ultimate dorm-room avatar. Meanwhile, the focus on African music went back South; the 1985 compilation The Indestructible Beat of Soweto became a crucial text, especially when it was reissued in the States the following year -- just in time to provide a vital context for the township music Paul Simon was lifting for Graceland.

But King Sunny Adé's impact and music still matters, in ways that seem clear in retrospect and still relevant now. Afrobeats has been a thriving genre across all borders for well over a decade, and it's not considered a niche NPR-audience strain of "world music" -- it's just more pop, and more readily accepted as such by a press more accustomed to the world-shrinking cultural exchanges the internet's accelerated. And it's the kind of phenomenon that highlights the necessity of imagining and building a future for pop music that isn't stagnating into diminishing reiterations of the Anglophone West's most-known genres. It's also exponentially easier to learn about African music without having to rely on a generalist perspective from outside; whatever mystery there might be behind it has largely been replaced by the work of dedicated outlets that center the music around its deepest community and diasporic roots while emphasizing how universally it can spread.

And even though I still can't find all the lyrics to Juju Music, I did find "Ja Funmi" on one of those old-school song-lyric databases that used to be the standard go-to before Genius showed up. The funny thing is that there wound up being two different translations. One seems more in keeping with the explanation I read from Adé. The titular phrase is translated as "fight for me," and it pertains to a certain sense of divine consciousness -- or consciousness itself as a form of divinity that guides our sense of empathy: "God created my brain to control myself. So this is the representative of my God. So you should protect me, you should fight for me." The pull quote up top there -- Eda mi ye o / Jaa ja funmi; "I understand it / Fight for me" -- comes from the Google translation. But Microsoft's Bing translator comes up with an entirely different meaning when you cut-and-paste the original Yorùbá: "I don't understand / Yes, I'm going to ask." These two translations clash in the most ironic way possible. But whether you understand it or not, it's wanting to understand that matters -- and it's the music happening behind the words that can help get you there.