Album of the Year is a recurring column that examines one album from each year of my lifetime and digs into what it means to me and others, whether it's a well-known popular favorite or a half-remembered niche obscurity. This installation concerns the line between absurdity and profundity and the funk legends who deliberately ignored it.

===

Sometimes when I think about the structures and the emotions and the attitudes of funk music, I return to a phrase that Dâm-Funk likes to use to describe it: "a smile with a tear." It's a pretty interesting way to frame it, especially since it reminds me of the title to the Roy Ayers LP "A Tear to a Smile". And then I get to thinking about the possible links between the soul-jazz/funk fusion Ayers mastered in the '70s and the meditative cosmic glide of Dâm-Funk's own synth-driven work, which is as good an answer as anyone's ever presented to the heretofore unasked question "what if Zapp was also Tangerine Dream." These are just a couple of the artists I listen to who get me thinking about how a genre that can be so frequently reduced to blunt-force simplicity by a mainstream conventional wisdom has often been some of the most elaborately, intricately complex and wide-open music there is. But it's worth taking a moment to acknowledge that you don't even have to dig that far into the outer reaches to find this out. Every so often it turns out that the canon's biggest figureheads really are there for a reason.

George Clinton's 1978 has to rank amongst the most preposterous batting averages of any auteur/bandleader/idea man/producer/songwriter/singer/etc. to ever operate in the album era, right up there with Prince in '84. Funkadelic's One Nation Under A Groove is the consensus fave, probably unsurprising considering it's the Clinton project most easily marketed as rock crossover. And it's an album, like a lot of Mothership-adjacent music, that I love a lot for its characteristic mixture of improvisation and groove, ridiculousness and insightfulness, heaviness and slipperiness. Among other things, the title cut's immortal, "Who Says a Funk Band Can't Play Rock?!" is the best fuck-you to genre boundaries ever recorded, and "Promentalshitbackwashpsychosis Enema Squad (The Doo Doo Chasers)" bodied Frank Zappa's entire career just by vamping through a hilarious extended riff on the philosophical concept of being a shithead. Bootsy's Rubber Band and their LP Bootsy? Player of the Year had jams for days, thriving off the continued creative emergence of Bootsy Collins' "space bass" technique and his brother Catfish's chicken-scratch-turned-eagle-claw riffs. Both the "girl groups" affiliated with the Mothership -- the Brides of Funkenstein (Funk Or Walk) and Parlet (Pleasure Principle) -- had striking debuts, the kind of breakthroughs that should've and could've made them candidates to be the proper heirs to Labelle if the cards had just been dealt a little more in their favor. When a solo album by synth maestro Bernie Worrell (All the Woo in the World) could be reasonably described as the sixth-best album Clinton had a hand in producing that year1, you know you're dealing with a creative juggernaut -- even if there's just enough exertion at the margins to make one wonder if a total burnout is just around the corner.

But there's no sign of fatigue on the LP that outdoes them all. Motor Booty Affair is the album I like to cite more often than most (Mothership Connection excepted) when it comes to embodying what funk is at its best. It's head music cleverly concealed within body music, where the familiar is rendered outlandish and vice-versa. It's collectivist while still providing a litany of distinct voices; you can be wholly moved by the musicians as ensemble yet still zero in on an individual's specific flourishes or exclamations or elaborate solos. It's one of those records that feels like The One is operating in the sense of binary language, where the accompanying 0 -- the open-ended not-yet-existing possibility of interpretation and reaction that the listener brings to it -- can unlock a whole new codex.

Of all the concept records concocted in the wake of Tommy, the stuff that Parliament got up to in the '70s ranks amongst the wildest and damn near stands alone in its dedication to worldbuilding. It's funny how they got ahead of just about everyone else in music with their whole vision of what is now dubbed (ugh) an "extended universe." And it's funnier still that Clinton used his more R&B-oriented outfit to do this instead of Funkadelic (whose concepts were usually a bit more self-contained), in opposition to the traditional preconceptions of "intellectual" concept-record "art" (read: rock) versus the more gut-feeling dance-first-think-later role that our more cement-eared rockists assume funk is supposed to fill.

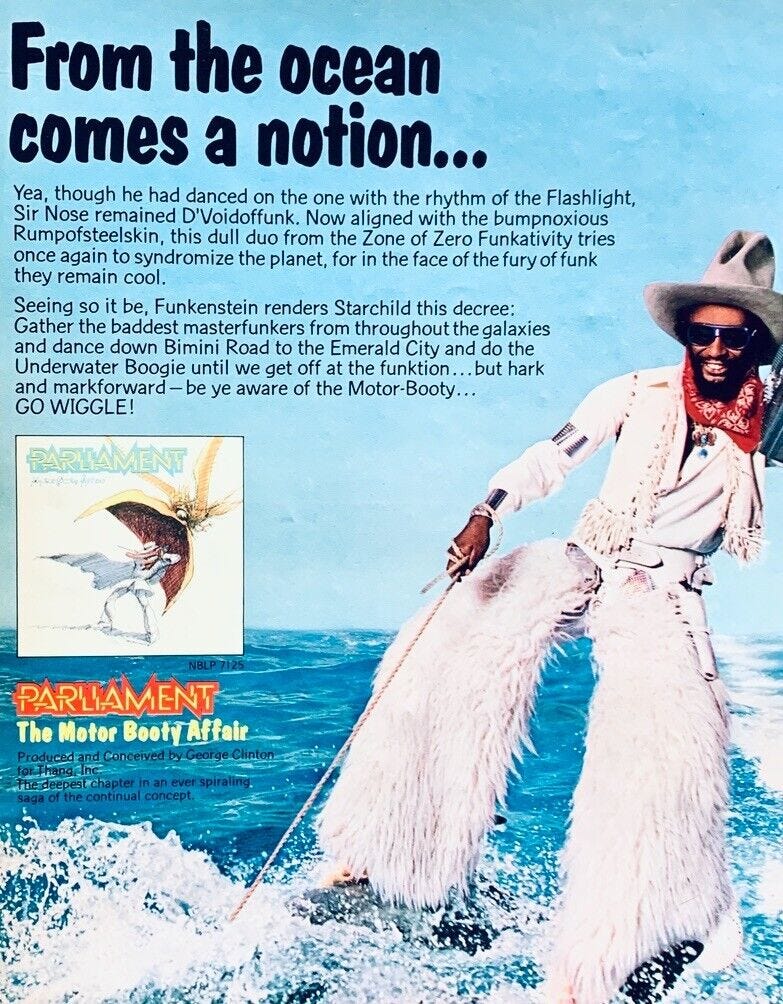

In terms of the wider culture, Motor Booty Affair feels like a spiritual bridge between Yellow Submarine (which Clinton cited as an influence, along with his general love of going on fishing excursions) and SpongeBob SquarePants (which I like to think is the Star Wars to this album's The Hidden Fortress). The story's place in the P-Funk mythos is pretty uncomplicated, at least on the surface, even if it takes a bit of knowledge to catch all the callbacks. There's a movement to throw a big party in the undersea kingdom of Atlantis, the purpose of which is to raise the city back to the surface using the power of dance. And since recurring foil Sir Nose D'Voidoffunk (introduced on previous album Funkentelechy vs. the Placebo Syndrome) resents the idea of being forced to dance, he works up a plan to sabotage this effort by smuggling in a robot of sorts, Rumpofsteelskin, a waterproofed Trojan horse who has "dynamite sticks by the megatons in his butt." But the extraterrestrial funk philosopher Starchild (from Mothership Connection) and the clones of Dr. Funkenstein (from guess which album) ruin his plans thanks to some clever manipulation of his insecurities. Since faking the funk means your nose will grow, and having a prominent schnoz is something of a detriment to underwater breathing, Sir Nose makes it clear he hates swimming as much as he hates dancing. But he's unceremoniously plunked into the ocean anyways, has to swim/dance just to keep moving, and discovers to his utmost horror that "it feels good," a phrase that has never sounded more like a wail of mortified agony.

This is one of the funny little tricks of P-Funk: they're one of those groups that is easily categorizable as "cool" but are actually something more complicated than that. They harbor a sort of benevolent eccentricity that has history in its predecessors (Sun Ra) and successors (De La Soul), people who put forth a form of Black art that defies the lowest-common-denominator stereotypes mainstream white culture expects while also goofing on the idea that there is a monolithic idea of their own culture. Latter-day pop culture, especially during an embarrassing stretch of the '90s and '00s, saw the '70s pimp/player figure as a sort of roguish folk hero and the epitome of a certain kind of cool unique to the era. But P-Funk's Sir Nose is a buffoon, a square who doesn't realize he's a square. He hates dancing because he is too self-conscious. It is easy to get a kid to dance but when the kid grows up and starts worrying about social status there's the risk of looking like an uncoordinated dork and so there are other more contrived forms of signaling "cool" that just wind up creating social discord.

Motor Booty Affair isn't necessarily trying to be cool, an approach which usually results in something that just is anyways out of sheer appealing uniqueness. It is both patenty ridiculous -- there are countless fish puns and at least half of them could be categorized as groaner "dad jokes" -- and sincerely beautiful, which I'll get to shortly. And since ridiculousness and sincerity clash with the more self-conscious and guarded forms of coolness, it lays bare how contrived the Sir Nose mode is: his attempt at coolness is only to be mocked or pitied because it's so often adversarial to the wrong people.

Then again, this is a perspective that is buoyed by a work of musicality that is cool in the sense that it's worldly and adventurous -- coolness not as cliquish of-the-moment trendiness but as the accumulation of genuine enthusiasms. P-Funk as a collective in their initial '70-'81 heyday hold a lot of power for me in that they are so easy to draw connections outward from. The more music I listen to, the more I return to this and reel from all the styles they fused and approaches they took, their ability to (no pun intended) synthesize multiple generations of tradition into something that must've felt entirely new when it dropped and still feels dislodged from any specific time.

In an immediate sense it's pretty easy to feel like this is a very '70s kind of album just from the recognizable tropes of the moment. There's the analog synths that Worrell and Junie Morrison drench the album in, the scattered references to Jaws and Charlie Tuna and Howard Co(d)sell, and the presence of a joyful form of countercultural vulgarity that hasn't yet approached the Tipper-panicking explicitness of pop in the following decade (including Funkadelic's own '81 kinda-sorta-genderqueer raunchathon "Icka Prick," for that matter). But Clinton's in his late thirties at this point, a Silent (lol) Generation member who cut his teeth on doo-wop and isn't averse to going further back even as he never stops moving forward. Opener "Mr. Wiggles" shows it off from the get-go, a deliriously updated Calloway/Ellington melange with a nod to formative '50s DJ personalities like Jocko Henderson, while also running his sensibilities through an Afrofuturism that invents cyberfunk before cyberpunk even existed. This is funk that swings, rocks, lurches, burbles, and glides into a techno-organic retrofuture, a time machine that breaks time. To quote that opening track: "We're swimmin' past a clock who has its hand behind its back."

So Motor Booty Affair is past-present-future-then-now-tomorrow all at once, which isn't that uncommon an approach for a lot of artists who attempt to reconcile tradition and iconoclasm. It just stands out here because it's so busy -- there are so many things happening, so many interlocking conceptual thrusts and unexpected detours and in-jokes and out-jokes that it's likely to bewilder you into paying attention. "Bewilder" in this case not necessarily meaning "confuse," but maybe more like a positive overwhelming. When you're occupied with trying to parse the relentless and rapidfire hooks and chants and gags it is driven home with an almost ostentatious display of melodic and rhythmic intricacy that seems almost supernatural. "Rumpofsteelskin" is just movement after movement and hook after hook, all of which would in isolation be the most memorable element of anyone else's song -- the chorus people wait for. But you don't have to wait, and there is no threat of boredom because pow, there's yet another deathless melody to burrow its way right into your skull. It's not mindlessly repetitive, it's meditative and recursive and communicative with itself.

And forget going down interpretive rabbitholes because the meaning will reveal itself through its impressionistic nature and meet your own interpretation. In the process of tearing Genius a new one, Never Hungover's Ock Sportello points out that the need to parse and deconstruct and tack citations onto lyrics is an impulse that gets in the way of music's direct emotional impact. Comprehension is a gradual learning process, not something to try and immediately figure out all the lore for. The Vivian Medithi sentiment cited in that piece about how deep knowledge isn't entirely necessary to enjoy something -- "babies love to dance" -- sounds like something Clinton himself would say. Even so, his tendency to engage in both idiosyncratic worldbuilding and truism/cliche/proverb-tweaking wordplay definitely rewards your attention. This album, like most great albums, isn't a puzzle, it's a tableau. Take it all in, and while you don't have to turn off your brain, at least take all those question marks you might have and straighten them out.

So before I finally get around to what Motor Booty Affair quote-unquote "means," there's one other thing that makes its presence and structure kind of impressionistic and overwhelming. You know all those Mothership Class of '78 artists I mentioned in the leadup to this? All of them are here. Everyone and then some. When P-Funk were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame there were sixteen members included and that's like maybe half of who shows up on here. Clinton stands out as a bandleader and a visionary not just for his own conceptual notions but because he pulled so many amazing talents into his orbit and e pluribus unumed them into an outfit where their specific talents were showcased -- and, this is the frustrating part, without necessarily always making it clear who did what. There are more than twenty credited vocalists alone -- including Overton Loyd in there somewhere, pulling extra duty after drawing the pricelessly wigged-out album art. And there are not one or two but several people swapping roles playing guitar and bass to go along with the Fred Wesley-led, Maceo Parker-featuring Horny Horns. (Seriously: Bootsy Collins is a bass player in your group and so is Cordell "Boogie" Mosson and then George goes yeah but let's see who else we can get some input from, get Rodney "Skeet" Curtis on the phone, and then it works?) There's even some claims that an uncredited Eddie Hazel is doing a bunch of work on this album contributing vocals and arrangements, and sure, OK, one of the greatest guitarists to ever live is just hanging out in the shadows putting in work. It's bananas.

So what you have is one of the most efficiently reinforced failsafe dream teams in all of postwar pop music. At this point the Mothership is a supergroup that took a whole bunch of the tightest musicians of their time, many of whom became virtuosos after toiling under the martial control-freak hyperprecision of James Brown, and told them to just go for it. There's too much sweat and too many hours on the odometer for these musicians to be anything other than incredibly locked-in, so all the sprawl makes for one of those rare situations where too many cooks make the best soup you've ever tasted. And the effect is that this is music that sounds overstuffed yet comfortable, a surplus of ideas pulled off with incredible efficiency, everything that technology and stylistic hybridization could afford them because they were on Casablanca and George knew how to get Neil Bogart to crack the vault open.

Still, with all those musicians at work, there's a pretty strong presence at the forefront worth pointing out. It's kind of dizzying, the miracles that Bernie and Junie could pull back when synths could only really sound like synths and not rinky-dink digital simulacra of other instruments. So much potential to sound annoying or dated or queasy is completely wasted, all because they wound up setting new standards for what levels of overdriven distortion could make for good proxy basslines and what kind of pitch-bending madness you could get away with if you had a catchy melody to back it up. 1977's "Flash Light" gave Parliament their first R&B #1 off Worrell's revolutionary multi-MiniMoog bassline, so it's not unprecedented, but put into wider practice here -- its rumbling glow driving "One of Those Funky Thangs" and roiling across the waves of "Aqua Boogie (A Psychoalphadiscobetabioaquadoloop)" (also an R&B #1) -- it becomes clear just how versatile that innovation could be. Funny enough, Junie also plays traditional bass on the title cut, and it's an absolute beast of a bounce; for a band that featured Bootsy Actual Collins it is kind of a coup that this is one of the three best performances on the instrument in the group's whole catalogue.

And then there's the voices.

I am sorry to do that thing people hate where you write a brief one-sentence paragraph for emphasis, but you know how I pointed out the twenty-plus singers on this album? This is where Motor Booty Affair starts to really sink its (fish)hooks into you. Clinton as multiple-personality master of ceremonies, the Brides/Parlet harmonies, the animated goofiness of Junie as he banters with worms even funkier than he'd ever imagined in his Ohio Players tenure, an entire choir of timbres and deliveries and octaves that range from exquisite beauty to suave hepness to gonzo bellowing and screaming and squawking. Pitched up, pitched down, filtered through submersed gurgles, sneaking in as background asides and busting out as unhinged proclamations -- it's enough to make Jim Henson and Richard Pryor exchange awed exclamations of damn. Even a cut like "Liquid Sunshine," where the performances are a little less over-the-top than the rest of the album, is riddled with near-subliminal layered backup vocals and interjections that the wildly fluctuating synth line buffets with the tides. It's so elaborate at times that some of the lyrics are still difficult to parse, which just means that this gives George Clinton something in else in common with Robert Altman besides a way with an ensemble cast.

This would be impressive enough if Motor Booty Affair was just a crazy little concept album about fish-people, one with some excellent party jams and silly jokes and a surprisingly affecting love ballad ("(You're a Fish and I'm a) Water Sign") that is as romantic as any song alluding to interspecies mermaid/dolphin sex could possibly be. (It's funny to picture in the literal sense, but a bit more fascinating to unpack as a metaphor for any number of possible kinds of mixed relationships that, in the end, find a commonality in being "two freaky fish.") But once the penultimate title cut ends, with all its celebrity-gala narration and its attendant excitement and the pure joy of its participants finding romance in the process, even with Sir Nose defeated and Rumpofsteelskin safely defused, there is something else to worry about. It's something of an inversion of "One Nation Under A Groove" -- the realization that while there is a massive collective effort to get this party moving towards total liberation, there's a lot of forces arrayed against it, clouding the waters and stoking fear and preying on peoples' hopes.

Motor Booty Affair was originally envisioned as a full-length animated feature, and "Deep" is the last-act climax. It is not another party, it's not a celebration, it's not even really a clear battle between two distinct factions. It is almost an intrusion of reality, the political agitation and satire heard in earlier works like Chocolate City facing the state of the nation and proclaiming: oh, shit. Because if you want to raise Atlantis to the top with the bop, there will be complications. Racial paranoia's the most striking one; turns out the population of Atlantis isn't entirely piscine and there are, among the inhabitants of this Bahamian-vicinity kingdom, a number of people from African tribes who took up residence in a less-tragic concept-record precursor to the stories told by Drexciya in the '90s. At one point someone affecting a nervously aggrieved white-guy voice stammers a bunch of there goes the neighborhood anti-integration panic ("I had to hire a spy"). And while the riposte to that is hilarious -- a mocking nasal nyeah-nyeah choral rendition of the '66 Batman theme -- the way the song's recurring it's got to be deep refrain takes a couple passes at slur-flinging frankness makes it feel like things hadn't progressed much further since Sly & the Family Stone's 1969.

But there's more than just casual individual racism or even small-scale institutional indignity to confront. The legal system is suspect ("You know this judge? He carries a grudge"). Raising a family in poverty is a nightmare; the moment where a woman just cuts the bullshit and shouts "my kids are starving" is a jolt. And it's obvious that the politicians who promise to solve it all are more enthusiastic about lining their pockets while the unions try to scramble for a piece of the pie. All that is steeped in interpersonal interrogations as to who knows who and where they stand ("I saw you only Friday, Joe, and just let me say/You tried to take me through a thousand confessions"), what resources they have available to try and preserve their autonomy ("I take my piece along for my protection you know/A man's got a right to be on top"), and how easy it is for people to turn against each other when battling the system proves tougher than it looks. It is such an incredible blend of cynical, frustrated bitterness and what-else-can-you-do-but-hope agitation, this confrontation of not just racism but encroaching neoliberalism that closes out an album otherwise filled with aquatic whimsy and myriad references to butts. It ends not on a triumph but on an acknowledgement that triumph is still far off. They're going to raise Atlantis to the top, just not immediately. Meanwhile, "we've got to keep on searching 'til we're totally free/But in the meantime let's say that we're deep."

In the final moments of the album, the fourth wall breaks and someone demands to speak not to Mr. Wiggles or Sir Nose or Starchild but to George Clinton himself. The sense of escapism dissolves and we're left with an effort to confront reality through an outlandish distortion of it that still holds truth and weight. It's pretty sobering when you stop and think about where this was all headed in 1978. On the right, the Moral Majority was making major inroads into an ultraconservative and evangelical agenda that would establish an incredibly, tragically effective backlash to the cultural advancements that made things like P-Funk possible in the first place. Meanwhile what pitiable fragments remained of left-populist post-New Deal socioeconomics were largely abandoned by a class of technocrats who redirected their efforts towards trying to figure out how to make capitalism more appealing. Then Thatcher. Then Reagan. You know and are currently living the rest.

Meanwhile, pop music's balkanization really started to set in. Disco became a dirty word that took down R&B with it in the process. Rock splintered into warring factions of punks and new wavers and heshers who eventually sent most of the truly creative efforts underground and to the margins. Jazz's pop-crossover dreams were smoothed out from heartfelt futurist fusion into placid elevator music. And not long after his creatively flourishing 1978, George Clinton was riding in the back of a limo with someone who introduced him to freebasing, and that was the beginning of the end for his top-of-the-world run as one of his generation's sharpest creative minds.

I come to all this via hindsight. I might've heard bits and pieces of P-Funk as a toddler, but my real education in funk came in the following decade thanks to the Minneapolis Sound heirs who found their own way to channel that feeling and vision. And like a lot of people my age, I found out about George Clinton's whole world through the artists he influenced -- primarily the hip-hop producers and MCs who grew up hearing his music and took it in about fifty different directions. But it says something when even a neurotic Midwestern white(ish) kid born a year before this album came out can find something in this music that sparks so much inspiration and emotion and enthusiasm. George Clinton is still with us. I saw him speaking in Los Angeles earlier this year and it was like witnessing someone taking stock of his life and marveling at just how much of a legacy he had built just by being fearlessly himself. And even as the seas rise, I still think Atlantis could emerge again -- it's still there, waiting for us.

in Clinton’s own memoir Brothas Be, Yo Like George, Ain't That Funkin' Kinda Hard On You? he refers to All the Woo in the World as one of his favorite side projects ever, so I’m probably due to give it another shot. I mean, it’s Bernie Worrell.