Album of the Year, 1983: Thin Lizzy, Life Live

But when all is said and done, the sun goes down

Album of the Year is a recurring column that examines one album from each year of my lifetime and digs into what it means to me and others, whether it's a well-known popular favorite or a half-remembered niche obscurity. This installment concerns the question of how dynasties end and what we do with what's left of them.

===

Something I've noticed while writing a few of these Album of the Year entries is that they center around not just records and bands I like, but the ways in which those records and bands get underestimated or dismissed. Maybe there's something about the overheated side of internet music discourse that's led me down a path where I wind up feeling like I have to pre-emptively be defensive of my tastes, at least whenever I suspect I have to make a strong case for something that could be considered kind of gauche somehow. But it also feels a bit like self-interrogation, about trying to reinforce the reasons music can appeal to me beyond the recognizable aesthetic thrill or nostalgic associations that a long-running familiarity has afforded it. And it helps when that music really does get a fair amount of shit from certain circles, even if some of those reasons are perfectly understandable.

So: let's talk about "hard rock." Think about how the term hangs there, looming imposingly yet deteriorating like some fading painted three-story-tall ad on the side of an old warehouse. It's a category that tends to stick in the craw when you invoke it to describe a certain strain of music that (by my estimates) peaked somewhere between 1969 and 1983 and has since been reduced to the brand of a gimmicky memorabilia-riddled restaurant chain. This is the stuff that was typically referred to as heavy metal when the parameters of that term were still being shaped, before the emergence of NWOBHM and Sunset Strip sleaze and the Big Four of thrash started splitting it all up into subgenre camps that eventually made the necessity of the descriptor heavy redundant and forgotten. "Hard rock" was turf that was already worn down by the time I hit my teens, a space where the frothy Bon Jovi and the visceral Guns N' Roses fought a polarized bi-coastal clash over who got to carry its fading torch into the next generation -- at least before the grunge/alt goldrush rendered the whole operation more or less obsolete. So I tend to reckon with this music as something from Before My Time, even if it's still recognizable and resonant. Which, like a lot of things I enjoy in this sense, means I regard it with a distance that's both necessary and a bit dissociative.

I feel a little ambivalent about hard rock, actually. The catch is that almost all of my reasons are almost completely unrelated to their aesthetics. As someone who really loves a lot of disparate genres, the stylistic provincialism on display in a lot of traditional hard rock culture -- dating back at least to the "Disco Sucks" late '70s if not earlier -- is hard for me to shrug off. So's the machismo, which was often reflected in some grotesque real-world behavior by its practitioners and can also betray a trad-value stuffiness that one would hope is anathema to the actual spirit of rock'n'roll. (Way to make me feel like a schmuck for enjoying Billion Dollar Babies, Alice Cooper, you transphobic dork.) The genre's rep as a whiteboys-only "cock rock" club may not be officially codified, but when a band like Death couldn't get a foot in the door and the Runaways were treated like the rock press's dry run for the worst Britney Spears discourse of the 2000s, that's difficult to shake, too.

For those reasons -- if definitely not those reasons alone -- a lot of critical appraisal of hard rock, while prone to shift with the successive standards of each generation, tends to be a bit too pat and dismissive to do its appeal any justice. When it was new, most rock critics scoffed at it as a step backwards from the strides taken by the poetry of Astral Weeks, the transgression of White Light/White Heat, and the psychodrama of Let It Bleed. (The fact that teens of the early '70s really loved Grand Funk Railroad was seen as something of a national crisis.) As it began to mutate at the cusp of the MTV era, the gripes shifted into the old saw this is why punk had to happen, evidence that rock had become decadent and complacent and the embodiment of its generation's worst values. And nowadays it seems like a hard sell when even the idea of starting a band with a guitar hero or two standing front and center seems anachronistic to most, while most of the heavy bands that do so tend to be brutal enough to make the likes of Deep Purple and Nazareth sound like ragtime by comparison. Every time I enthuse about some bicentennial-era LP that seems specifically engineered to come out sounding best through the speakers of a shag-carpeted custom van, I imagine myself being eyerolled at by the composite picture of every 22-year-old who is earnestly annoyed by boomer cringe. To be fair, that eyeroll could just as easily come from a 45-year-old. Or a 70-year-old.

It's not just me being self-conscious, though. Because a lot of mainstream pop culture, even the affectionate tributes, seems to lean towards the idea that hard rock is a joke. In the 22 years between This is Spinal Tap and Tenacious D in The Pick of Destiny it became clear that you take this stuff seriously at your own risk, even if you love it. Ozzy became a reality-show goofball, Van Halen were parodied as coke-addled clowns on Metalocalypse, and the people who revere Blue Öyster Cult as America's greatest art-metal pioneers are outnumbered at least 500 to 1 by the people who immediately conjure up mental pictures of Will Ferrell manically thwacking a cowbell at Christopher Walken's behest. Also KISS exists. So there's that. Between its fluctuating unfashionability amongst more highfalutin music-geek circles, the latent-in-plain-sight silliness that proves to be impossible to resist as comedy fodder for the irony-poisoned, and the actually troubling tendencies of the men who dominated its milieu, peak hard rock often feels hard to love on its own terms no matter how much I try to tune all that extraneous bullshit out.

Still, my ambivalence is less to diminish the existing works of the hard rock canon than to wish that canon was a lot more spacious. There's still a lot of power in that continuum of blues-rooted rock gone feral, the tendency that Hendrix and Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath supercharged, and the ensuing wave of Generation Jones-aimed hard rock produced some of the most joyously shameless music of its time. Like a good action blockbuster or a pro wrestling blood feud, its best examples are sincerely guileless enough in their thrills to not only make you not care if it's dumb, but challenges the idea of what we even consider "dumb" and why. There are a few hard rock bands that make me feel this way, where I want to scrape away all the troubling associations and the bad jokes and the remnant classism and contempt for the uncultured folks of flyover land and just take the music for something pure. And no hard rock group does a better job of making me forget all that extraneous baggage than Thin Lizzy.

Not that it's easy. Like many other bands of their kind, they've been dragged into a reputational space where sincere enthusiasm brushes up against punchline status. You probably know the latter mode well, at least if you're online enough. Their biggest hit is the premise of a popular 2015 dril tweet ("its fucked up how there are like 1000 christmas songs but only 1 song about the boys being back in town"), and while I know it's the utmost form of pedantry to fact-check a dril tweet, that hasn't even been true since 1979. That same year, Timothy Faust wrote an article for Vice that professed a sincere love of "The Boys Are Back in Town" in the process of also rendering it into an annoying gag at the expense of a bunch of bar patrons who he forced to listen to it several times in a row. He seemed clearly unafraid of being labeled a poseur, calling their all-killer-no-filler album Jailbreak "thoroughly nonseminal" and claiming "I've never listened to that album the whole way through, and by the grace of God I know I'll never need to, for I know that Jailbreak features at least two songs: 'The Boys Are Back in Town,' and whatever song comes after 'The Boys Are Back in Town,' which reminds you that you need to hit rewind." Imagine admitting, in public, you don't fuck with "Emerald"! Goddamn, dude. At least now I know who the real heads are. Then there's that one stale gag, the "why don't they make the entire airplane out of the black box" of rockcrit: "'Tonight there's gonna be a jailbreak/somewhere in this town?' Have you tried -- heh heh -- checking the jail???" Buddy, take one look at Jim Fitzpatrick's futuristic-sci-fi-dystopia album cover and consider the possibility that, a'la The Village in The Prisoner, the jailbreak is happening "somewhere in this town" because the entire town is a jail. (As Sean T. Collins reminded me on Bluesky, it is not a far-flung concept for an Irish band in the '70s to pull off.)

Sorry. I just had to get that out of my system. A more measured rebuttal to all that nonsense did exist for a while a couple decades back, when indie-friendly bands like The Hold Steady and Ted Leo and the Pharmacists did their service by wearing their still-lingering influence on their sleeves alongside more hesher-friendly groups like Mastodon. (Granted, this happened years after Metallica cut a version of the traditional Irish song "Whiskey in the Jar" that was largely based on the 1972 Thin Lizzy interpretation that made it one of their early cult hits, and it was memorable enough to distract people at least a little from how embarrassing late '90s Metallica were getting.) There are worse fates for a band than being a household name to many but an if you know you know to a smaller subset, the band with two or three songs a lot of people know and a dozen or two more that you wish they did. The sticking point is that you never know where a conversation about them will go, and whether or not you can get people to believe you when you say how amazing they sound to you. So this odd space between being a famous band that sold a lot of records but not, like, AC/DC numbers can feel like an unknown quantity outside your own head.

What I think I did in response was to form my own notion of what I wanted Thin Lizzy to represent to me, and I think one of their strengths was that they make this seem feasible, or even part of the plan. A lot of this is down to Phil Lynott, whose strengths as singer, primary songwriter, and bassist seem to be amplified by a certain sort of romanticized vision -- the swaggering arena rock star as a simultaneous tough guy/sensitive soul -- that he seemed to pull off with a casual ease that eluded most of his peers. Sadie Sartini Garner's Pitchfork Sunday Review of Jailbreak theorized that this was a sort of kayfabe pseudoauthenticity, not in the sense that Thin Lizzy's badass attitude was a false front per se, but that their music was just too good-natured to make them feel truly threatening. That scans to me -- it's a toughness less offensive and resentful than defensive and resilient, not so much gang warfare as gang summit. Lynott cuts a fascinating figure because he's the proto-metal version of the James Dean sensitive-hoodlum archetype, and his experiences of being mixed-race in Ireland fueled a self-awareness of how his identities intersected that emerged, compellingly, in the music itself. (It's worth noting that the b-side to the original 1972 7" of "Whiskey in the Jar" is a Lynott original titled "Black Boys on the Corner" that is maybe half a tab of acid away from early '70s Funkadelic.) His biological parents weren't always there to raise him -- his father was absent, and his mother would send him to live with his extended family when he was still fairly young -- so he was raised not just by grandparents and uncles but by pop culture, by movies and rock'n'roll. Damn, this guy seems lonely, I've thought sometimes listening to some of Thin Lizzy's more melancholy ballads, and even with my comparatively stable family situation I recognized that similar ache and the power of escapism from my own childhood.

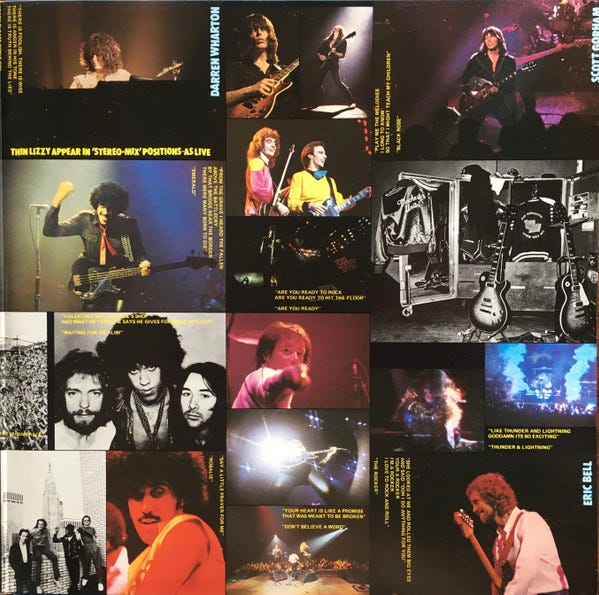

The band he led is also an absolute beast of a group in just about all its configurations. His own bass playing technique was upfront and spotlit, played with a pick but boasting the same depth of force that Larry Graham and Louis Johnson did with bare-thumbed slap bass. Its low-end clobber is a marked but crucial contrast to the way he sings -- suave but vulnerable, ferocious yet empathetic, given to elastic phrasing and delivery that countered the drive of the beat with casual off-kilter timing. And the core lineup of the mid '70s that boasted the competing/complementary lead guitars of Scott Gorham and Brian Robertson gave Lynott the ideal accompaniment to match his restless vocals; their solos are molten on the anthems and poignant on the ballads. My most direct route to familiarizing myself with their breadth was hearing the best material of their first five years wrangled into the behemoth that is Live and Dangerous, the fan-favorite double live that, despite its composite multi-venue setlist and its alleged overdubbed pseudo-verite nature, might be the ne plus ultra of what I want in a hard rock concert recording. (I actually spent much of this year immersing myself in the absurd eight-disc Deluxe Edition, which if nothing else proved that these guys were consistent.) That one's heavy on the studio albums that represent their peak to me: 1975's Fighting, the '76 two-fer of Jailbreak and Johnny the Fox, and the transitional-yet-powerful '77 Bad Reputation, the last to feature Robertson as half of the twin-lead-guitar attack with Gorham.

But the album I'm looking at here is something entirely different -- a counterpart from half a decade later, a version of the band that's simultaneously slicker and more elegaic, because it's the conclusion of a long goodbye. Life Live was recorded at the Hammersmith Odeon, which makes this the second concert recording from this venue in the early '80s that I'm using to make a point about the legacies of bands who peaked between the Ford and Reagan administrations. Unlike Blondie, however, Thin Lizzy knew they were on the way out. At this point this just isn't the same band anymore, and not merely because the lineup had gone through numerous personnel-juggling permutations since '78. Gorham and Ultimate Breaks and Beats-immortalized drummer Brian Downey stayed with the band until the end, and that core of the group was still enough to maintain their sonic identity for a while, even as they shifted noticeably to adapt to the impossible-to-ignore impact of punk and NWOBHM. John Sykes, who was still a teenager when Jailbreak came out, filled Robertson's old role en route to a fateful stint with Whitesnake; he'd succeeded a string of guitarists from the briefly-returning-prodigal-son Gary Moore (who left after 1974's Nightlife and returned briefly for 1979's Black Rose: A Rock Legend) to Dave Flett (who you might know from his ecstatic-panic solo on Manfred Mann's "Blinded by the Light") to Snowy White (who gigged with Pink Floyd during the late '70s in their live shows and had one of the finest performances in rock history to ever be confined entirely to the 8-track format).

If that reads like the machinations of a band trying to pull themselves out of a slump, that's backed up more concretely by the studio albums from this stretch. Their post-Live and Dangerous discography marks a noticeable decline, driven in part by Lynott's growing problems with alcoholism and other addictions. Black Rose has far more high points than low, but I can hear some hints of fatigue setting in that are a lot harder to hide by Chinatown the following year. And 1981's Renegade is running on fumes; opener "Angel of Death" is the first-track peak, and once you get to Side B you can tell they're not exactly capable of filling the same niche as Judas Priest or Iron Maiden. While there's no clear consensus on their studio finale Thunder and Lightning, I do think it pulled them up from a nosedive and provided a strong coda to their career. Ironically, that's largely because Lynott so effectively laid out the fact of the matter in his songs that he was losing control of himself, a sentiment that was already clear by Black Rose cut "Got to Give It Up" and would permeate the mood of their final album. Which brings us to this snapshot of their 1983 farewell tour.

Greg Prato's AllMusic review is harsh in keeping with the typical negative critical reactions to it -- he calls it "polished pop gloss" and shrugs off the songwriting of their '80s material as not on par with the old stuff -- but I hear clarity where he hears gloss, and their songwriting deficiencies are overwhelmed by the sheer force of the performance. As far as the former's concerned, I still think it's a bit odd to hear synth solos on Thin Lizzy songs, but Darren Wharton makes it work; his performance on opener "Thunder & Lightning" and "Angel of Death" do a more intuitive job of integrating prog-noodling keyboard barrages into hard rock than, say, Judas Priest's Turbo would three years later. And their '70s material that carries over from their Live and Dangerous set is either run through with that same sense of velocity and power ("Jailbreak," "Are You Ready", "The Boys Are Back in Town"), or tweaked in ways that sound less like mersh-minded dilution and more like entirely new perspectives: "Don't Believe a Word" is slowed from a pec-flexing boogie to a meditative gaze at the night-lit horizon, while "Still in Love With You" -- one of the earliest and easily one of the best hard rock power ballads -- slows its already contemplative tempo into an exhibition of negative (head)space that sets up an absolutely searing tearjerker of a Sykes guitar solo. That they close the whole thing out with a version of "The Rocker" that reunites Gorham, Sykes, Moore, Robertson, and first-incarnation '69-'73 guitarist Eric Bell, is one of the most effective ways I've ever heard a band in swan-song mode put an exclamation point on their legacy.

Meanwhile that accusation of diminished songwriting strikes me as pretty curious because Lynott has always been a songwriter who, rock-poet rep notwithstanding, effectively leans on straightforward, no-bullshit simplicity. Frankly, it's probably the reason a lot of people try to wring comedic riffs out of Thin Lizzy's music. On paper, even some of their best material can read kind of prosaic and flat. "Still in Love With You" is one of their all-time most beloved showcase moments and it puts all its weight behind lines like "After all that we've been through/I try my best, but it's no use/I guess I'll keep on loving you/Is this the end?" "Waiting for an Alibi," one of my favorite of their bad-times-in-a-dicey-situation character study songs, describes the trouble a bookie's gotten himself into with the couplet "It's just that he gambles so much/And you know that it's wrong." (While it doesn't appear in this setlist, my all-time favorite clunker is from Johnny the Fox ballad "Sweet Marie," where he sings about being "Somewhere out in Arizona/Such a long way from California." I guess it might feel that way on a tour bus, but maybe don't use that line about two states that share a border.) And as uneven as their '80s material is, the examples in this setlist are generally in keeping with that mixture of directness and simplicity -- the overtones of religious struggle in "Holy War," the sympathetic look at the troubled youth of "Renegade," the reckoning with a toxic relationship in "Sun Goes Down" -- that made his own struggles sound universal enough that they almost felt obvious.

But that obviousness is both necessary and integral. Here's the thing I've been building to about the critical dismissal and general underestimation of hard rock: its appeal is hard to grasp if you're trying to be hyper-literate and go by Dylan/Springsteen standards, but incredibly easy to understand in terms of pure emotion. Rock lyricism doesn't have to be complicated poetry, and it doesn't have to be self-consciously aware of itself when it's straightforward, either. But there is a power in someone singing words that sound like the first thing to immediately come to mind, and expressing them with such an intense conviction and operatic audacity that is extremely rock'n'roll -- and R&B and pop while we're at it. I am actually willing to recognize that I enjoy Thin Lizzy in a way that means engaging with this rockin'-the-fuck-out twin-guitar kickass bad-boy swagger music on terms that fit the original definition of, uh-oh, poptimism. In that sense, I mean that a performance of caricaturized authenticity based around broad tropes and elementary lyrics can be every bit as vital and exciting as your more respectable Graham Parkers or Elvis Costellos -- often moreso if you're more in the mood for gut-punch emotional appeals than brow-arching cleverness. Whether they're delivering a call to arms or a cry for help, Thin Lizzy want you to comprehend it fully, and it's their music that adds the full spectrum: the solos that startle you with their elaborate heightened delirium, the rhythms that grab you by the throat as a way to make the backbeat ripple down your spine, the vocals that turn common phrases and even cliches into the most heartfelt thing you've ever heard. And even at a low point, Lynott made damn well sure he brought everything he had to the stage.

The conclusion of Thin Lizzy's story after Life Live happens in a familiar way, but it's no less tragic for it. Even though Lynott would live nearly a decade past the 27 Club, a combination of health issues caused by a heroin addiction claimed his life in the first week of 1986. He was 36 years old. Despite the usual stories about rock star excess and womanizing that swirled around him, there was something about his rep that transcended the typical hotel-trashing fuck-and-run live-fast-die-young mythos. (One post-mortem story I love: in 2012, Lynott's own mother objected to Mitt Romney's campaign using "The Boys Are Back in Town" during the RNC because Phil would've objected to the Republican party's anti-gay and pro-rich policies.) I haven't even touched on the solo career he'd struck out on, and where it could've taken him beyond the hard rock that his career was built on -- the striking nods to punk and new wave and synthpop on Solo in Soho and The Philip Lynott Album promised a much more idiosyncratic '80s than he'd had a chance to fully explore. But who he was, and what he represented, still needs a few more worthy heirs in this world. This town's big enough for more than just some boys, and the best way to maintain the liberatory feeling of busting out of jail is to give that freedom to everyone.

Also want to add that the Dirtbombs covered Lynott’s “Ode to a Black Man” on ULTRAGLIDE IN BLACK.

I got heavily into Thin Lizzy thanks to Mick Collins and his cover from Phil Lynott's solo album, that's been mentioned. They had a great run, and were one of the best hard rock bands with equal amounts emotion and cred.

On another note, what do you think about Rory Gallagher? They have very different tones but maybe it's the time and being from Ireland, there's something there. Gallagher is like Chandler and Lizzy is more Hammett, in my opinion. And that's not a dig at either.